Harry Thurston Peck

by Joseph S. Salemi

A few weeks ago my wife asked me to find a book for her via the internet bookstores. This is now the only practical way to locate out-of-print texts, and I had done the same thing several times in the past for her and for other family members.

She wanted a book that she remembered from her grade school days—a child’s fantasy titled The Adventures of Mabel. My wife did not know the author, or the date of publication, or anything else about the book other than that it was a children’s text about a young girl and her adventures with several talking animals, and that it had a gray cover. But her memory also told her that the prose style of the book was definitely from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century.

When I started my search it did not seem promising. The search engines at the internet bookstores showed countless books with the name “Mabel” in the title, and many with the added word “Adventures.” Nevertheless, it became clear after some time that the book in question was The Adventures of Mabel, written in 1897 by Harry Thurston Peck. In addition to this first edition (which Peck published under a pseudonym) there were a surprising number of newer editions, going right through to the 1960s. The book seems to have been one that many school districts liked, and wanted in their school libraries, and this kept the thing in print for decades after the author’s death.

Eventually I located an edition of Peck’s Mabel that had a gray cover, and that seemed to fit the timeline of my wife’s grade school days. I immediately bought it, and when it arrived she told me that it was precisely the edition that she had read as a young girl. I’ve done this for her three times before, with other hard-to-locate texts, and she now thinks of me as some kind of magician or wizard. I told her that it was not me, but the world-encircling scope of the internet bookstores that made these finds possible.

Anyway, I became curious about the author Harry Thurston Peck, of whom I knew nothing at all. There was a fair amount of information on-line about him. He only wrote two children’s books, and Mabel had apparently made a huge hit. All of his other works were scholarly, since he was a classics professor of very high abilities. The more I read about him, the more interested I became.

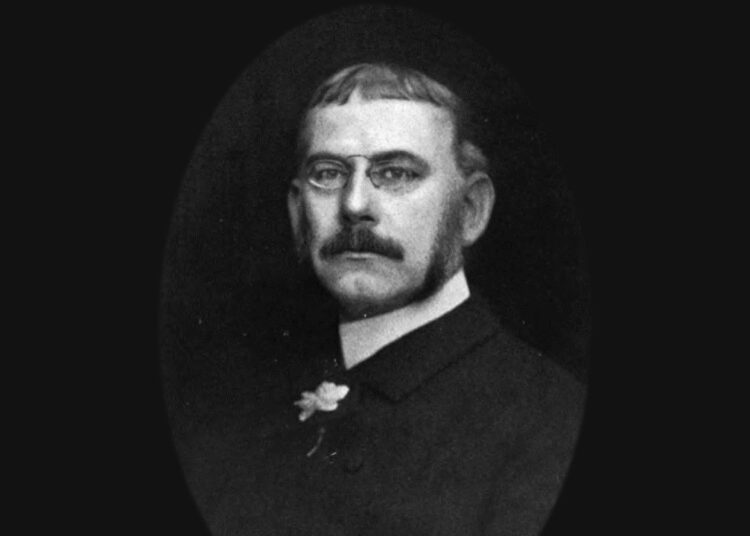

Peck was born in Stamford, Connecticut in 1856. He attended Columbia University, and while still a young man he joined the faculty of that school, and quickly became a highly respected classicist of the first rank. His scholarship and publications were so highly regarded that he was appointed the Anthon Professor of Latin Language and Literature in 1904. His list of publications was impressive: he edited Suetonius, wrote a History of Classical Philology, translated Petronius Arbiter’s Dinner of Trimalchio, produced a text on the pronunciation of Latin, and put together several anthologies of translations. He was also a historian, an essayist, a travel writer, and the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Dictionary of Classical Antiquities and other encyclopedic study guides, all before the age of forty-five—an amazing feat for anyone in Classical Studies.

He also wrote one small book of poetry, Greystone and Porphyry, published in 1899 by Dodd, Mead & Company here in New York. Having learned about Peck’s life and career, I wondered if this book of verse (which was mentioned in the list of his publications) was worth reading. So when I saw that a copy of his Greystone and Porphyry was listed for sale at one of the internet bookshops, I just had to buy it.

That small book is why I’m writing this essay. But before I get to Peck’s poetry, let me finish with his life story. It is a sobering tale.

By 1904 Peck was in his prime, and at the very pinnacle of his career. His scholarly reputation was beyond reproach. He had a tenured position at a major Ivy League university. His writing brought him substantial income, as well as fame. All signs pointed to him having many more years of success, prestige, publication, and material rewards.

It was not to be. Peck’s wife divorced him in 1908, on the grounds of “desertion,” though that may have simply been a cover for some other issue. In 1909 Peck married again, and this is what lit the fuse to disaster. A third woman, who had read in the papers of Peck’s second marriage, brought a breach-of-promise lawsuit (for $50,000) against him.

In those days, a breach-of-promise suit could be initiated on several grounds, not just on an open violation of some written contract or agreement. If you had sent a woman love letters, or had written her poems that could be construed as “romantic,” or if you had “courted” her publicly, or if she had become pregnant and named you as the father, or even if an unfounded rumor of your engagement to her had been bruited about in gossip, she could launch such a suit against you. This was the era of Anthony Comstock, and any offense against the purity of womanhood aroused fury, especially in the courts, which (as the writer Ernest Belfort Bax pointed out) tended to be highly biased in favor of female complainants.

The sum of $50,000 was immense at that time, and the scent of money was very strong for some lawyers, particularly if the proposed defendant was a man of significant wealth and property. The lawsuit was ruinous for Peck in both a reputational and a financial sense. The woman’s attorney offered as evidence many passionate letters and poems written by Peck to the lady, as well as her testimony about their relationship. Although Peck was acquitted because of various uncertainties of interpretation in the written evidence, he lost in the court of public opinion, since the case had become a huge public scandal, with the newspapers excoriating him as a cad and a Lothario.

Peck declared bankruptcy, since his defense had cost him practically his entire fortune. But even worse was this: he was summarily dismissed from his position at Columbia University by the school’s puritanically tight-assed President, Nicholas Murray Butler. By 1910 Peck had taught at the university for twenty-eight years, and had honored his department with the unbroken record of his scholarship. But back then tenure was de facto, and not official. Even though Peck and Butler were personal friends of long acquaintance, Butler fired him simply out of moralistic outrage, and a terror of bad publicity. When Professor Joel Spingarn (a brilliant scholar in the school’s Comparative Literature Department) spoke up defending Peck and questioning Butler’s unfair actions, Butler fired him also.

Most of Peck’s friends and colleagues deserted him, as did his new wife. He could not find any job in academia. He could only live by getting small writing assignments that paid practically nothing. He dropped out of sight and became a homeless vagrant and eventually wound up in Ithaca, New York, where he fell gravely ill in 1913. Both his wives worked to help his recovery, and he survived. But he was broken. By 1914 he was back in his home town of Stamford, living in a cheap rooming house. There, on March 23, 1914, he put a revolver to his head and committed suicide.

This was the man who wrote The Adventures of Mabel, the book that delighted my wife when she was in grade school, and no doubt has delighted hundreds of other children ever since it appeared in 1897. It probably has had many more readers than any of Peck’s specialized scholarly texts in Classical Studies. The character Mabel is a polite and well-spoken little girl who is intelligent, curious, and brave.

But what of that small book of poetry (Greystone and Porphyry) that Peck wrote? Well, let’s turn to that now, and see what it can tell us.

It’s short—only 62 pages. The book is a lovely duodecimo, with deckle-edged laid paper of heavy weight, and a rubricated title page. The covers are hard and gray, with the title and author’s name in flourished gold capitals, and with a strange herbal design as the chief decoration. It contains eighteen poems, mostly short, with the last one being longer than the rest. Of these poems four have Latin titles, although all are in English.

The subjects can be surprising. There is one poem on Jefferson Davis, and another on Otto von Bismarck, and the final poem is a lengthy complaint against the power of Money. But let’s take a look at “Heliotrope,” which is of a more personal nature.

Heliotrope

Amid the chapel’s chequered gloom

She laughed with Dora and with Flora,

And chattered in the lecture-room—

That saucy little sophomora!

Yet while, as in her other schools,

She was a privileged transgressor,

She never broke the simple rules

Of one particular professor.

But when he spoke of varied lore,

Paroxytones and modes potential,

She listened with a face that wore

A look half fond, half reverential.

To her, that earnest voice was sweet,

And, though her love had no confessor,

Her girlish heart lay at the feet

Of that particular professor.

And he had learned, among his books

That held the lore of ages olden,

To watch those ever-changing looks,

The wistful eyes, the tresses golden,

That stirred his pulse with passion’s pain

And thrilled his soul with soft desire,

And bade fond youth return again,

Crowned with its coronet of fire.

Her sunny smile, her winsome ways,

Were more to him than all his knowledge,

And she preferred his words of praise

To all the honours of the college.

Yet “What am foolish I to him?”

She whispered to her heart’s confessor.

“She thinks me old and grey and grim,”

In silence pondered the professor.

Yet once when Christmas bells were rung

Above ten thousand solemn churches,

And swelling anthems grandly sung

Pealed through the dim cathedral arches;

Ere home returning, filled with hope,

Softly she stole by gate and gable,

And a sweet spray of heliotrope

Left on his littered study table.

Nor came she more from day to day

Like sunshine through the shadows rifting:

Above her grave, far, far away,

The ever-silent snows were drifting;

And those who mourned her winsome face

Found in its stead a swift successor

And loved another in her place—

All, save the silent old professor.

But, in the tender twilight grey,

Shut from the sight of carping critic,

His lonely thoughts would often stray

From Vedic verse and tongues Semitic,

Bidding the ghost of vanished hope

Mock with its past the sad possessor

Of the dead spray of heliotrope

That once she gave the old professor.

The structure of this poem is simple: a lovely young female student and an older professor feel a mutual attraction, but say nothing, since each assumes that any relationship between them is impossible. The student thinks she is too immature and foolish to expect any attention from him, and he thinks he is too old and unattractive to stir her interest. She has deep feelings for the man, and he feels the same for her, and wishes that his youth could return.

Nevertheless, one day during the Christmas holidays she leaves a spray of heliotrope on his desk. She never comes back to school, and we are told that she has died. All have forgotten her, except the old professor, who keeps the dried spray of heliotrope as a remembrance of an imagined hope that never materialized.

The poem is typically late nineteenth-century in diction, style, and sentiment. There are verbal touches that we might find clichéd, such as “her girlish heart” and “tresses golden” and “her winsome ways.” The references to “Paroxytones and modes potential,” and to “Vedic verse,” clearly indicate that the poem’s professor is a Latinist and philologist, just as Peck was. Is the poem autobiographical? Perhaps, but the theme of hot sexual sparks between student and teacher goes as far back as Abelard and Heloise. The whole thing may be a fictive invention.

Note that each stanza is composed of two tetrameter ABAB quatrains, with alternating masculine and feminine endings. The rhymes are perfect except for “churches” and “arches,” which might be due to an earlier pronunciation from Peck’s Connecticut background. One major issue is the length of the poem, which today would be considered excessive for such a minor subject. And there is a kind of straitlaced sentimentality in the piece that practically strangles any genuine sexual expression. It is a polished poem, but very much of its time and place.

Another interesting poem is “Immemor” (unmindful, or unremembering), of nine rhyming couplets. It also deals with love and loss.

Immemor

I stood beside the sleeping sea

Whose waters murmured drowsily,

And Night behind her dusky bars

Looked through the lattice-work of stars.

Then she I loved was by my side

And all the world seemed glorified

When, stooping down, with dainty hand

My name she traced upon the sand,

And said that so Love’s magic art

That name had graven on her heart.

Slow crept the waves along the sand,

Soft lapped the waters on the land,

Till all her work of love and pride

Was lost beneath the swelling tide.

To-night I walk the shore alone

And, thinking of the years long flown,

Recall the tide of time that came

And blotted from her heart my name.

This is another poem on love, but one that clearly echoes Spenser’s Amoretti 75, and more obliquely, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18. But Peck’s poem is darker—the waves wash away his name, and there is no expressed hope of any remembrance for himself, nor does he promise literary immortality to the girl addressed. It is another poem of deep regret and sorrow over thwarted desire. The poem’s language shows that Peck had significant talent, as in “the lattice-work of stars” and the use of “Slow” and “Soft” as adverbs.

Melancholy pervades all of Peck’s compositions. The poem “In Aeternum” (into eternity) is not just lugubrious, but even reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe’s obsession with premature burial.

In Aeternum

When I was still a living man,

And ere the years of life were spent,

My fearful fancy often ran

On what would be my punishment.

For I had sinned as only few

In human form have sinned as yet;

And, though suspicion slept, I knew

That God would wait and not forget.

This hideous form it seemed to take,

That I was doomed where none could save

To die yet not to die, but wake

Amid the damps that fill the grave.

And oftentimes in fearful dreams,

When all was dark and I was hid,

I heard my own half-stifled screams

From under neath the coffin-lid.

Five days ago life left its cell…

Long shuddering silence… then I knew

That I had died, and oh, too well

That all the dreadful dream was true!

Black darkness weighs my eyeballs down,

The leaden coffin’s close embrace

Keeps pressing, like a devil’s crown,

The cere-cloth on a ghastly face.

I struggle hard to stir, to speak,

To beg of Christ another fate,—

To cry aloud, to curse, to shriek,

To thrust away the leaden weight.

O depth of agony profound!

No heart to break, no tear to shed,

No tongue to voice the awful sound

Of him who dies and is not dead:

But o’er and o’er and o’er and o’er

I think of all the ill I did,

That holds me down forever more

Beneath the leaden coffin-lid.

This is a frightening and upsetting poem, and if it is autobiographical then we see Peck as a man tormented by unspoken guilt, and driven by a Connecticut Puritan conscience to an unshakable sense of his own depravity. What could he have possibly done that would evoke this nightmare of living death? His life story suggests a weakness for women, and relationships with women are what led to his downfall.

I’ll quote from one more poem, the strange “Unter den Linden, 1890.” It is set in Berlin, in the year that a young Kaiser Wilhelm II angrily dismissed his Reich Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. This act has generally been seen as a major mistake that set the stage for the catastrophe of World War I, since it resulted in the subsequent alliance of France and Czarist Russia that forced Germany into a two-front war in 1914.

Poets are sometimes said to be prophetic. I think a good case can be made that Peck’s piece, published before the start of the twentieth century, shows that kind of vatic power.

The poem is a twelve-stanza narrative, each stanza composed of two ABAB quatrains, exactly like “Heliotrope.” The scene is the Café Bauer, on the famous and picturesque Unter den Linden boulevard, where persons are relaxing towards the end of day. The city is described as flushed with national pride, beautiful, prosperous, and profoundly warlike.

Suddenly the sound of drums and bugles announces that the Kaiser and his retinue are approaching. And as the retinue comes into sight, Peck describes the figure of Kaiser Wilhelm II:

Cold eyes, set lips, a restless glance

That wanders in uneasy quest,

With looks that like a living lance

Blaze from beneath the helmet-crest;

Upon that face as on a page

Has nature stamped with cruel truth

The heartlessness of cynic age,

The reckless insolence of youth.

What morbid motive half defined,

What œstrus-thought that stings and stays,

Goads on his restless, brooding mind—

This sceptred Sphinx of modern days?

Is it ambition’s poisoned wine—

The throb, perchance, of ceaseless pain—

The spark of genius half divine—

The burning of a madman’s brain?

And this is he whose sword and pen

All Europe eyes with bated breath,

Whose word can arm a million men,

Whose nod can hurl them on to death:

A nation’s life, a nation’s ease,

The honour of a nation’s name,

The awful fates of war and peace,

All centred in a single frame.

This description of the Kaiser captures perfectly the unease and apprehension felt everywhere in the Western world about Germany’s new emperor—his unpredictability, his inexperience, his disregard of ministerial advice, his sometimes truculent nationalism, and most especially his undiplomatic impulsiveness and boyish militarism. Peck ends the poem with a reminder of the terrible potential enemies that Germany faces, and the major wars that may have to be fought:

To scourge the land with sword and flame

The northern Cossack grimly waits;

The Dane remembers Düppel’s shame,

The Austrian broods o’er Königgrätz;

While on the hills of fair Lorraine

That front the slopes of Vendenheim—

A tiger with a slender chain—

The Gallic foeman bides his time.

Stout-hearted sons of Fatherland!

Who kneel to God but face the foe,

And side by side together stand

To sing the song of long ago

That, rising from a myriad throats,

A nation’s battle-hymn divine,

Thrills on the ear like bugle notes:

“Fest steht und treu die Wacht am Rhein!”

This is a perceptive comment from Peck about the dangers that Imperial Germany faced in 1890, when there was fierce resentment in France against the seizure of Alsace-Lorraine, the silent threat of Czarist expansion in the east, Danish anger over the 1864 battle of Dübbel, and Austrian bitterness over their severe defeat at Königgrätz in 1866. Germany had been united by the victories in these wars against France, Denmark, and Austria, but it had come at the cost of lasting European resentment and revanchism. Peck seems to have been well up on current events and political personalities, and despite his distrust of the Kaiser, was favorably disposed to the German nation itself. When he quotes a line from the German patriotic song (“Strong and loyal stands the Watch on the Rhine!”) to end his poem, he is praising young Germany for its strength and military victories, while warning about the dangers that surround it, and about the unstable character of its new emperor. Peck sensed future disaster for the world, and expressed it in this poem.

I was pleased and surprised to find this obscure poet, whose tragic life cast a shadow over his scholarly achievements. And finding him and his poetry was a pure accident—the side result of doing an internet book search. And this has confirmed me in my strong opinion that a good poet must utterly put out of his mind any thoughts or concerns about his audience. You will never know who your audience might be! Your poems could float around for 126 years—as Harry Thurston Peck’s did—before a sympathetic reader in New York came across them while trying to please his wife.

Joseph S. Salemi has published five books of poetry, and his poems, translations and scholarly articles have appeared in over one hundred publications world-wide. He is the editor of the literary magazine TRINACRIA and writes for Expansive Poetry On-line. He teaches in the Department of Humanities at New York University and in the Department of Classical Languages at Hunter College.

I am as enamored with Peck’s poetry as I am with your fabulous essay on his life and work. I am familiar with the legal atmosphere that permeated, and in some sense still permeates the predilection for women to vindictively pursue perceived paramours and certainly husbands. A lot depends on which state legal action is filed. I savored the flow of his poetry in both 16 and 17 syllable two-line counts. This has opened a new vista for me, since I have constrained my own poetry to 14 syllables maximum thinking that might be too long while I often attempt to cut out the extra syllables. My thought process was thus truncated. I wish I could think of the entire verse as 32 and 34 counts. Maybe you can help me on this. “Heliotrope” spoke to me as in my university teaching experience I have had similar thoughts about the possibilities, because I have been approached after lectures with someone having a sparkle in their eye. I never received flowers, though. “Immemor” with time and tide erasing sand script is a fairly common theme, but Peck’s stands out to me as a beautiful remembrance. “In Aeternum” is such a dark, morose poem, yet the way it is phrased, particularly in the at the end is virtuoso verse. His characterization of Kaiser Wilhelm II really resonated and had a brilliant ending, ““Fest steht und treu die Wacht am Rhein!” which I had translated “Stand fast and true, the Watch on the Rhein,” until I saw your translation which is a good one. I thank you for your revelation and sharing of Peck’s poetry.

Thank you, LTC Peterson. I have had much pleasure in researching and writing about Peck (who was totally unfamiliar to me six weeks ago), and I am gratified to know that you took similar pleasure in this essay. There is a special joy in finding a new poet whose work you have never read before.

Peck’s legal troubles all occurred in the state of New York, where at that time, I believe, the only legal justification for divorce was proven adultery. Since his first wife claimed “desertion,” it’s likely that she made her claim for divorce in some other state, and the action was not contested by Peck.

About the number of syllables in a line of verse, it all depends on which meter you are using, and if you have any substitutions. All of Peck’s poetry that I quoted was in iambic tetrameter, so as a rule his lines have eight syllables. He has nine if the line has a feminine ending. And he has only a few trochaic starts to his line. All his verse reads very smoothly and regularly, and as you say, taking two lines as a group each couplet would have 16 or 17 syllables. That’s perfectly normal, I think, and there’s no need to limit your couplet groups to 14 syllables.

The story of Abelard and Heloise should be required reading for anyone entering the teaching profession. It points out two elemental problems: the tendency to hero-worship in some young women, and the positively electric effect that young female flesh can have on an older man. In my dad’s fruit-and-vegetable store, we sometimes warned the customers: “Look, but don’t touch.” That’s good advice for teachers.

It’s true that there is a sadness about Peck’s poetry. But his ability to write compelling prose was also phenomenal. He wrote a very long history (400 pages!) of American political campaigns and conflicts from 1885 to 1900. You’d think that such a book would be as boring and dust-dry as the subject sounds, wouldn’t you? But I can attest that the thing was so compelling I just couldn’t put it down. I got so wrapped up in the narrative that my wife had to order me to stop reading, and come to the table for dinner

Thank you, Dr. Salemi.

Where to start? My sixth-grade teacher, Miss Asbury, once read her class, a chapter at a time, a novel-length story about some species of mythical “little people.” If I had remembered any of the identifying features (e.g. author or title) I would have read it to my own children when they were growing up. As it happens, there is a shitload of this kind of children’s literature, with some of it (e.g. The Lord of the Rings) even fit reading for adults. Sadly, I cannot recall many of the titles.

I liked Peck’s poems, and would not mind reading stuff like his today, on this website. As you must already know, there are plenty of classical scholars who have written good poetry in English. On my own bookshelf I could point to Richmond Lattimore’s The Stride of Time.

Kip, could the book that you refer to be “The Adventures of the Teenie Weenies,” by William Donahey?

I do not know about Kip’s reference, but I still have two copies of the Teenie Weenies somewhere. One with a green cover and one with a tan cover.

Roy, when I was a kid in the 1950s “The Teenie Weenies” was still running as a comic in the Sunday papers. I loved the stories about a tiny race of people living in old shoes and empty boxes. The guy who invented and drew the comic did it for fifty years. By the way, if you still have those two books they are now quite valuable.

Could be, Joseph, but sheesh! it was sixty-five years ago..

Thank you, Mr. Salemi. I enjoyed reading your essay.

I’m very glad to have pleased you.

In case you haven’t discovered them yet, the sellers at AbeBooks.com have been my best on-line source for out-of-print books for years. Happy hunting!

Yes, I have used ABE frequently. The others are Amazon, Alibris, E-bay, Powell’s Books, and some smaller outfits.

Fascinating Joe, quite fascinating; the life and the poems you explore.

Thank you, James. I really enjoyed writing this piece.

I’m still reading, but noticed there are several tragic similarities in Harry Thurston Peck’s life and the lives of Edgar Allen Poe and O. Henry.

By the way, O. Henry is not well known in the UK, and for its short story competition a British writing magazine was recommending its readers to check out the works of O’Henry, apparently believing he was Irish.

“O. Henry” was just a nom de plume for William Sidney Porter. But if one didn’t know that, it might seem that it was an Irish surname. Later on, the name “O. Henry” became the name of a candy bar. I have no idea why that happened.

He took on the name O. Henry when he was in prison for embezzlement and started writing. As I recall, he needed money for his sick wife.

Mr. Peck may have been treated unjustly and brought to ruin by the cancel culture of his day, but your discovery has introduced his poetry and writings to a new audience. I was also curious about Professor Spingarn and learned that he eventually became a co-founder of the publisher Harcourt Brace in 1919; also, he was involved with the NAACP, of which he was president from 1930-39. Not bad for one of those white Jewish men that the modern left loves to hate.

Spingarn wrote a book on The History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance, and it was so impressive that the philosopher Benedetto Croce arranged to have it translated into Italian, and he maintained a correspondence with Spingarn for many years. That correspondence was collected and eventually published.

Joe, this is one of the most beautiful essays I have had the privilege of reading. I like the lovely book-search introduction that led you to a treasure trove of literary gems you have shared in shining words that have me both reveling in the talent and hand wringing at the injustice that consumed this extraordinary writer – a fate of despair that appears to plague many great writers.

I also love this essay for the hope it affords every writer whose words float like twinkling stars above the fray at a time when people’s eyes are drawn gutter-ward… one day a curious Professor, on an errand for his beloved wife, might spot my quirky offerings and breathe life into them long after their author has departed. Joe, thank you!

Thank you, Susan. We never know what will happen to our poems — who will read them, who will comment on them, how future generations will react to them, and what reputation we as poets may have. All of it is out of our control. The work of the great Roman poet Catullus barely survived at all. In the fourteenth century, someone found an old manuscript of his work in the city of Verona, propping up the broken support base of a wine barrel. That’s why we have his poetry today.

Thank you, Joe, not just for the essay but for the discovery of Peck, the research you did into his life, and the presentation of some of his fine poetry.

I am quite moved by the entirety of this scene — the poet and your discovery of the poet. A story which travels through time as a 21st Century poet discovers an obscure 19th Century poet and gives new life to not just his work but his very existence. Your appreciative essay is a fine tribute to this man who might otherwise have remained unknown to the vast majority of us. It is a bit like digging in one’s backyard and making an important archaeological find. There is something inherently romantic about this discovery of unexpected great things, like the recent discovery of a previously-unknown Mozart serenade at a library in Leipzig. (I sometimes wonder how those 16th Cetury farmers in the Bay of Naples felt when they ploughed their fields and discovered a forgotten ancient Roman city.)

I am also moved – and angered – by the biography of Mr. Peck. He was obviously a great scholar and a great talent and yet his life was destroyed by what we now sneeringly refer to as “lawfare.” The idea of suing for “breach of promise” is so archaic and unfair as to make abundantly clear why this type of lawsuit has been mostly either made illegal or has been abandoned. Reputations ruined along with personal finances and careers for something inherently personal and which did not involve a real wrong. Leftists may drool at the prospect, but it strikes me as a hateful and inhumanely puritanical form of punishment for actions and choices which are simply human. I’ve never heard of a sadder ending for a poet. Even an early death like Keats’ is preferable.

The poetry is a pleasure to read. The conceits are stellar, although I find the language a bit stilted (forgivably so) as representative of the Victorian aesthetic. I think each of Peck’s works is wonderful, eliciting chills with “In Aeternum” and appreciative sympathy for the sand imagery in “Immemor” (which echoes the concept of the Buddhist mandala – an artistic work made of impermanent sand with the expectation of its being destroyed by wind and rain.) While my half-Prussian heritage makes me forever fascinated by the Kaisers, I’m most intrigued by the interplay of points of view between the professor and the student in “Heliotrope.” It probably is indeed a fiction but that makes it all the more entertaining and true. His observation of the psychology of these characters is acute. And I love the symbolism of the flower that indicates a turning towards the sun, even if for just a short time. A very fine metaphor for love which never quite connected.

All told, a wonderful and moving find, Joe – the poet and his work. Thank you for this. It gives a writer hope that his work might not sink into permanent obscurity. One can never know.

Brian, I am glad that you have enjoyed this essay. Thank you for your appreciative words. The whole thing was quite a surprise for me too, since I knew nothing at all about Harry Thurston Peck. At this point I have bought and read three of his prose works in Classics and history. His book on “The History of Classical Philology” (from the ancient world up to the death of Theodor Mommsen) is meticulously detailed and amazingly well written, and it explains everything so lucidly that it could serve as a vademecum for all Classicists.

The “breach-of-promise” action was, I believe, originally intended as a protector or safety net for naive young women who were the preferred prey of unscrupulous seducers. But it was very quickly weaponized by some women as a way to entrap an incautious male into marriage, or to bilk him of cash if he were recalcitrant. The glaring bias of early twentieth-century courts (both here and in Great Britain) favoring female litigants in marriage, divorce, property division, and breach-of-promise cases was a true example of early “lawfare” motivated by a radical ideology (suffragist feminism). Even though the judicial system back then was almost totally male (from the bench to the appellate courts to the jurors to the court clerks and the lawyers), this ideology had deeply permeated society. Greedy gold-diggers and common sluts could get rich by vamping an inexperienced guy.

The danger of a breach-of-promise suit was responsible for the nearly complete disappearance of the love-letter tradition among courting couples. No sane man dared to put anything into writing! You couldn’t even send a Valentine card without worrying about it being used as evidence in court. Peck seems to have disregarded the danger, and he paid for that mistake. He may have been too honest and trusting.

Peck’s poetry is very good, if not of the highest rank. But it does show how widely the knowledge of poetic form and craft was in those days. English poetry was an established and traditional art with centuries of work behind it, it had clear stylistic rules and genres and diction, and there was no damned William Carlos Williams around, screaming that we as Americans had to forget all of that stuff. I think that recognizing this fact when I read Peck’s small book of verse gave me the greatest pleasure of all, even if it was nostalgic.

Thank you, Joseph, for for both your essay and the comments afterward. (I’ll give you partial credit for those your effort brought forth from others.) This piece was a pleasure to read, regardless of the interesting subject–a brief but vivid example of humane letters.

To comment further for a moment on “In aeternam,” it made me wonder about the life, and especially the end, of Nicholas Murray Butler.

In 1939, the poet Rolphe Humphries wrote an iambic pentameter acrostic poem, with the first letters of the poem’s lines spelling out the sentence “NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER IS A HORSE’S ASS.” The editors of “Poetry” accepted and published it without realizing that the message was there. They were deeply embarrassed by this, and formally apologized to Butler in the next issue of the magazine.

Lots of people hated Butler.

I came across Peck’s poetry about ten years ago, looking through poetry period shelves in an academic library. That’s another rare way for dusty publications to get readers!

I copied “Heliotrope” because I liked it, and because I was doing research on refrain poetry, I hoped I could somehow classify it in the ballade family. English-speaking poets often keep the refrain (only the final word is essential) and expand the number of rhyme sounds they allow themselves. I have a feeling Peck may have started the poem with the ballades of near-contemporary English writers (Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, Austin Dobson, W. E. Henley) in mind. Eight-line stanzas are standard. But it turned out too long (six stanzas is the maximum), and he dropped the refrain from stanzas where aging teacher and young student break into their different modes of passion. As a whole, “Heliotrope” becomes a flower piece with secret significance partly taken from the “language of flowers” books of the time. I happen to have one, in which the heliotrope means “devotion.” This ultimately accords with realized emotions of both figures in the poem, as well as with unrealized relationship potential. Flower language was acknowledged to be a way of saying the socially unspeakable.

The student/teacher situation has innumerable manifestations, as I could attest from my experience of being both at the same time. I’ll suggest, as a good comparison with Peck’s “Heliotrope,” the much anthologized “Elegy for Jane” by Theodore Roethke. It features the same very close physical and psychological observation of the girl by the man. The difference is that Roethke more vaguely hints at the student’s feelings, while Peck has her declare them, but not openly, within the poem. The girls in both poems suffer unexpected death. Roethke then outlines his unrecognized yet not incomprehensible grief: “I with no rights in the matter, neither father nor lover.” That could cover an enormous range of relationships involving attraction and affection between student and teacher.

Margaret, thank you for your comments. I’m happy to know that someone else has looked at Peck’s work, and has appreciated it.

The complex language of flowers, and the many books of that time that outlined it, make a fascinating subject. So little of that complexity survives in common usage today (red roses for love, lilies for death, and a few others). “Heliotrope” as devotion makes perfect sense in this poem — both student and teacher are devoted to each other, even if only through silent regard and esteem.

I didn’t think of Roethke’s elegy in connection with this piece, but you correctly point out some parallels. Both girls die, both professors are upset, and both professors sense some unbridgeable gulf between themselves and the students. We could also add that both poets describe the girls as energetic, active, vivacious, and a bit wild. But in the very nature of the case, this is likely what an older professor would feel concerning students decades younger than himself. They are active and lively — he is not quite so.

Thank you for bringing up the poem’s possible link with ballades of that time, and how the refrain may have been deliberately minimized. It shows that Peck was not afraid to handle his poem in whatever way was aesthetically the best choice, even if he had to alter a fixed form.

Thank you for this wonderful piece. It provided delightful surprises at every turn, both about the tragedy of Peck’s life (which was particularly interesting to my lawyer’s eyes — and thoroughly well-described), as well as exposure to his works. “Heliotrope” I agree was a bit stilted in places, but its theme urges us to read something of Peck’s personality into it. “Immemor” and “In Aeternum” were lovely, and I’m grateful that you brought these to a wider readership. I especially like your words of encouragement at the end. It is presumptuous for us to second-guess Fate, so we should put our work out there and let her do the rest.

Since Peck’s works are in the public domain, I tried to see if they were posted online, but alas! I can only find hard copies for sale. I encourage you to upload “Greystone and Porphyry” to Wikisource, to allow the world to read the full volume.

Thank you, Adam. Other readers in the legal profession (like Brian Yapko) were also interested in the litigation that brought about Peck’s tragic end. After posting this essay, I did learn that Peck’s first wife had obtained her divorce out of New York State (in South Dakota). I think many persons (both male and female) who sought divorce in those days did it on the false but nebulous grounds of “desertion,” so as to avoid the public embarrassment of admitting to sexual infidelity by their spouse or by themselves.

”

Peck’s book “Greystone & Porphyry” is on-line at the Hathi Trust, which puts up copies of rare books held in university libraries. Here is a link to the full book, in faithful photographic images of the entire text, from cover to cover:

babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hxdamv&seq=1

Read the two poems on Jefferson Davis and Otto von Bismarck. Peck was very attuned to politics and political behavior.