The One That Got Away

Nelson Cedrick Thunderwood, a Colonel in the army,

has served his country faithfully for thirty-seven years.

I doubt if there’s a medal Colonel Nelson hasn’t won…

he’s earned the admiration and respect of all his peers.

In the mess hall, during lunch, a private wandered passed,

and an irritated Thunderwood assailed the new recruit!

“You there, private,” he exploded, “give me fifty push-ups.

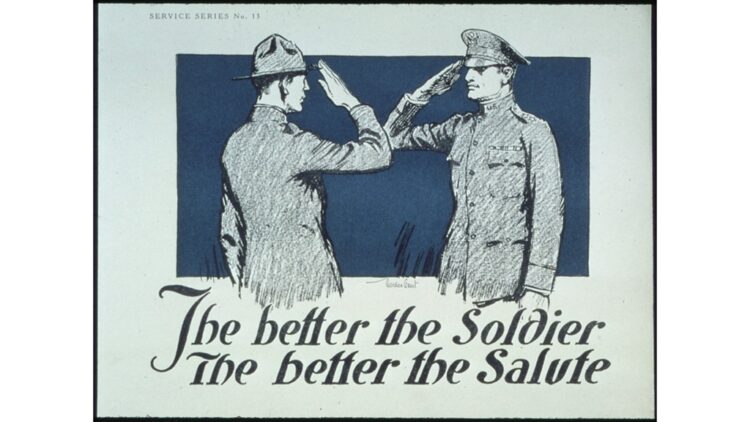

When you see a Colonel you’re expected to salute!”

“I was just about to, sir, but I couldn’t find my glasses!

I couldn’t tell your rank,” he claimed, “I hope it’s not too late.”

“I should give you 30 days,” the angry Colonel growled.

“So tell me, just how long were you expecting me to wait?”

“Only 3 or 4 more feet and I’d ‘ve been saluting,”

swore the frightened private as he stood there like a stone.

Thunderwood ignited, “So you couldn’t see my stripes,

but would have been saluting—as you should have—had you’d known?”

“That’s a fact, sir,” he replied, “if my eyes were better

I’d have been saluting long ago, and that’s the truth!”

Somewhat disinclined to take his word for what he’d told him,

Thunderwood, not trusting him, began to quiz the youth!

“So tell me, how’d you qualify to actually join the army?

A soldier needs keen eyesight if he’s going to shoot a gun!”

“I’m a bit surprised myself,” the private would explain,

“perhaps they only let me in ‘cause I’m the General’s son!”

“You don’t say,” the Colonel fired back in great dismay.

“You don’t mean to tell me you’re the son of old J. P.?

I’m sorry that I yelled at you, my boy, and it’s forgotten.

Forget the fifty push-ups. Would you care to dine with me?”

“With respect, sir, Daddy thinks I’m joining him for lunch,”

he quipped, “so I best not, but thank you just the same.”

“I understand,” the Colonel said, “and kindly tell your father,

‘Hi,’ from me! And by the way, son tell me what’s your name?”

“My name’s J.P., Jr., sir,” the youngster proudly crowed,

“and I will try my very best to make Dad proud of me.”

The Colonel firmly shook his hand and said, “I’m sure you will,

and I would not have yelled if I had known how bad you see.”

Moments later—after they had gone their separate ways—

the Colonel paused and thought a bit then glared around the room,

searching hard to find the kid an’ have the MP’s grab him,

bursting at the seams to seal the sneaky booger’s doom!

After he’d dismissed him, and of course he’d disappeared,

he realized that he’d been duped and all but blew his lid

knowing the line-o’-crap about his sight was total bull,

remembering J.P. Balderdasher doesn’t have a kid!

Mark Stellinga is a poet and antiques dealer residing in Iowa. He has often won the annual adult-division poetry contests sponsored by the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop, has had many pieces posted in several magazines and sites over the past 60 years, including Poem-Hunter.com, PoetrySoup.com, and Able Muse.com—where he won the 1st place prize for both ‘best poem’ of the year and ‘best book of verse.’

I loved your story, but there are a couple of things you may know and ignored or may not know. 1.) A Colonel must retire after thirty years of service (not 37) unless he is on the promotion list to General. 2.) A Colonel would be recognized by the silver eagle insignia of both shoulder epaulets, not by stripes. Stripes are for enlisted. Other than those facts it was enjoyable.

The 37 years is an easy fix, Roy, (27), but the ‘stripes’ faux pas is obviously a bit more complicated. 🙂 Never having served, most anything I’ve ever penned that ventures into a military issue will be likewise boogered. Thanks for commenting –

I enjoyed the poem. Coincidentally, a very similar story comprised an early episode of the TV show Gomer Pyle U.S.M.C. starring Jim Nabors.

I can’t help but wonder, Russel, if that particular G. P. U. S. M. C. episode might have inspired this fun little piece! Connie and I never missed that series. 🙂 Glad you liked it –

Mark, this is a good story of a quick-thinking enlisted man getting away from the belligerent notice of an officer. And I like your choice of belligerent names for the colonel and general. However, I notice even more breaches of military customs than Roy did, maybe because I was enlisted and he was an officer. This should have been an outdoor story, because enlisted are required to salute upon meeting an officer outdoors. Indoors, enlisted personnel must rise to attention when an officer enters a room, until the officer says, “At ease.” You may have seen indoor salutes in movies or TV, but that happens only when a military man (regardless of rank) is reporting to another, or otherwise wanting his official attention. And in a mess hall, your colonel ordinarily could have read the fractious soldier’s name from his uniform, but I’ll assume you chose an occasion when civilian clothes were allowed. You’re right about officers demanding due honors, but they often get them with mere sharp glances at offenders. You’ve made this amusing with deliberate exaggeration!

Margaret – I’ve watched too many movies & television programs in my 7 decades that, like my poem, often unwittingly disregard military protocol. Never having served, this is all news to me, but I’ll gladly settle for ‘amusing with deliberate exaggeration’. Thank you –

Great fun, Mark. Just what the doctor ordered.

Thanks for the read.

Precisely as I intended, Paul – and you’re welcome – thanks.

I enjoyed this very funny poetic story, Mark. Your taking liberties with protocol mirrors the cheeky character of the private in your story. I categorize this story as one of “fictive-military humor involving the endearing rogue serviceman.”I have never seen such a character in poetry before, but your private has a long and storied list of predecessors ranging from Luther Billis in “South Pacific” and Ensign Pulver and Mister Roberts in “Mister Roberts” to the wise-cracking William Holden character in “Stalag 17.” The fast-talking conman/serviceman was a popular staple on television as well with such wily characters appearing n MASH, Hogan’s Heroes going back to Sgt. Bilko. I can trace this archetypal character back to Shakespeare’s Falstaff at least, though I would not be surprised if he appears in earlier works as well. Shakespeare no doubt got the idea from somewhere.

“Great minds think alike” ya’ know, Brian, but I just can’t see Willie as a plagiarist, and I’m very flattered by your group of top-notch cinematic comparisons. Connie and I watch a LOT of Hogan’s Heroes every year and have enjoyed all of those excellent films. So glad you enjoyed it – 🙂 Take care, Mark

A toe- tapping, highly entertaining delight of a poem, Mark! I’ve also enjoyed the comments section. Thank you very much indeed for brightening my day!

I’m always delighted to brighten your day, my dear, Connie and our 2 families loves my ‘funny’ ones as well – got a ton of ’em…