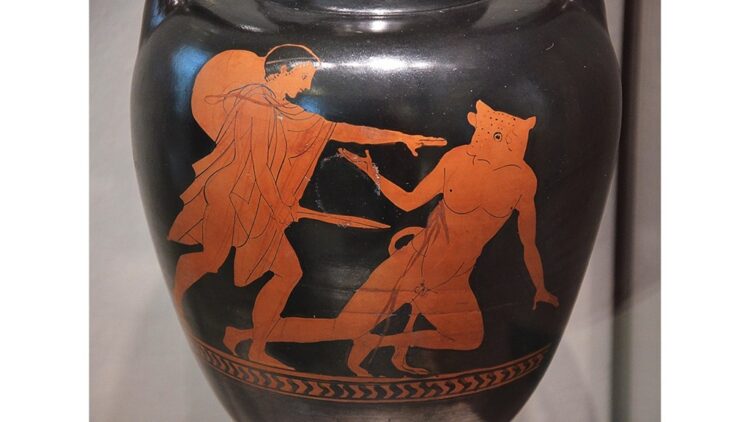

Theseus in the Labyrinth

—from “The Slaying of the Minotaur”

As Theseus crossed the threshold, Minos told his men to shut the door.

The heavy clang caused all to think the brave lad would be seen no more;

But there, inside the darkness, clever Theseus’ plans were taking shape,

As nimbly to the door he tied the thread by which he would escape.

He did not put the ball of thread into his pouch, but held it fast,

Unwinding it with every step, that it might bring him back at last.

He felt his way along the hall, the path before him black as pitch,

And crept with care, lest he should bang his head or fall into a ditch.

From time to time, his path would end; then left or right, he’d have to go.

At times, he seemed to go in circles, but he really could not know.

For nothing but the sense of touch enabled him to find his way;

His other senses only brought distress, confusion, and dismay.

For every now and then, he heard a fearsome growl or wailing cry

And knew it was the Minotaur, whose torment made it wish to die.

At other times, he smelled an awful odor he could barely stand

And knew that somewhere in the dark, the loathsome beast was close at hand.

His blindness was unbearable! It was a torture going round

In circles, never knowing with his next step where he might be found.

The darkness and the odor and the howling left him out of breath,

As desperately, he kept on pacing, fearful in the face of death.

Then suddenly, he turned a corner, and he found himself within

A chamber dimly lit somehow by sunbeams streaming, pale and thin,

He felt relieved to see the light, and in that room, he wished to stay,

But hearing footsteps drawing near, he felt compelled to slip away.

Once more plunged into deepest darkness, turning round and round in fright,

He fled, trapped in a madman’s nightmare, doomed to drift in endless night.

He flew on blindly like a bat, until he saw a light ahead,

Then rushing toward it, found himself within the room from which he’d fled.

This time, the chamber was not empty, for the few faint beams that shone

Within that room revealed to Theseus that he was no more alone;

For in the corner, hunching over, was a large and hairy form,

And Theseus, peering close, could see on each side of its head a horn.

He gasped and roused the hulking beast, who raised its head in shocked surprise,

Then bared its teeth and growled and glared at him with two red glowing eyes.

So Theseus turned and tried to run, but in the murky hall he found

The creature at his back, who grabbed him by the neck and threw him down.

Before he could withdraw the dagger from his pouch, the creature fell

Upon him with infernal strength, just like a demon out of hell!

To keep its fangs from tearing at his throat, the hero had to take

In his strong hands its deadly horns, to twist them with a violent shake.

The struggle was intense as Theseus sought to break the monster’s neck

By meeting its attack with equal force that held them both in check.

He felt its hot breath on his face, He saw its eyes like coals afire;

Then sharply jerking one horn down, he triggered its volcanic ire.

The creature roared in rage, confounded, then retreated to rebound

In one last, lunging fatal blow; but at that moment, Theseus found

His hand upon the handle of the burnished dagger at his side,

So drawing forth the knife, he braced himself for what would soon betide.

The only thing that he could see, now that the beast had pulled away

Were flaming eyes that grew in size as death drew nearer to its prey.

Then with a snort, the monster sprang upon him, but to its surprise,

With one swift thrust, its victim plunged a piercing blade between its eyes.

At once, a doleful cry resounded through those hellish halls, as now

The wounded beast, struck blind with pain, fell back, as blood gushed from its brow.

It staggered in the darkness, pacing round in circles as it tried

To stand; but soon, it lost its balance and collapsed at Theseus’ side.

As life drained from its prostrate form, the creature, with its dying gasp,

Looked straight at Theseus with sad eyes, and held his forearm in its grasp.

Its fury seemed to die away, as fitful waves subside at sea

When tempests leave, and in their wake, a gentle tide rolls peacefully.

Its savage features softened, as without a word, it seemed to say,

“I bear no grudge, for you have freed me from my misery this day.”

At last, the massive form was still, its tortured cry would sound no more

Within those halls, for death had come to claim the dreaded Minotaur!

Then swiftly, Theseus felt the floor to find his precious ball of thread,

For when he ran into that hall, he dropped it, as in fear, he’d fled.

On finding it, he stood and started back the way he’d been before;

But first, he drew the dagger from the forehead of the Minotaur.

With bloody hands, he headed back, as eager fingers led the way

Through countless twisting pitch- dark halls to freedom and the light of day,

He could not see the path ahead, but bright thoughts filled his heart with light:

“The deed is done! The demon’s dead! The day has dawned to end the night!”

He carefully retraced the steps that brought him to the monster’s lair,

Led by the blessed string that took him to the iron portal where

His labyrinthine quest began; so having reached his journey’s end.

He banged upon the door to see what timely help the gods would send.

He did not wait for long, for after several knocks, he heard the sound

Of iron scraping iron, and he knew the door would soon be found

Wide open, with the bar removed, and someone on the other side—

A friend or foe, elated or enraged that he had not yet died.

A sense of joy filled Theseus’ heart as sunlight streamed into the maze,

For there stood Ariadne, like an angel sent on heaven’s rays.

She looked in awe at Theseus, then exclaimed, “My Lord, you are alive!

Have you disarmed the deadly sting that waited for you in that hive?”

Then looking down, she saw the bloody dagger in her hero’s hand

And marked his blood-stained tunic—that was all it took to understand

That Theseus had succeeded in his task—he’d crushed the viper’s head!

Now nothing would remain the same, for lo! The Minotaur was dead.

“No one has ever passed through this dark door,” she said, “and come again

To see the light of day once more, restored unto the world of men.

Their lives to hate were sacrificed, on vengeance’ blazing altar burned.

You only have come forth alive, and by your courage, freedom earned.

“My Lord, my father surely will reward you for this valiant deed.

He’ll see the gods have aided you in this endeavor to succeed

And will reward your valor and your willingness to give your life

To save your fellow countrymen by making me your happy wife!

“O Theseus, I desire to go with you to Athens, there to stay,

To reign beside you as your faithful queen and never go away.

Please take me with you as your bride, and swear to live with me always

And I will lie down by your side and make you happy all your days!”

At these impassioned words, the brave young hero knew not what to say.

“O precious girl, because of you I live to fight another day,

I overcame the odds through your twin gifts, the dagger and the string,

I’m here, therefore, because you saved me. Come now, take me to the king!”

Martin Rizley grew up in Oklahoma and in Texas, and has served in pastoral ministry both in the United States and in Europe. He is currently serving as the pastor of a small evangelical church in the city of Málaga on the southern coast of Spain, where he lives with his wife and daughter.

Nothing about saving a sample of the blood so the DNA could be analysed to work out the beast’s ancestry.

If they did trace the DNA, they would find that the Minotaur was the stepson of Minos, the king of Crete. According to the ancient myth, Minos´ wife conceived the Minotaur through an unholy union with a bull! As a result, the child born to her had the body of a man and the head of a bull. In shame and anger, King Minos then had the labyrinth build by the master architect Daedalus to hide the monster from human sight. Later, he used the labyrinth as a prison in which to confine his enemies and sentence them to death at the hands of the dreaded beast.

Well told Greek tale in verse and rhyme.

Thank you, Ray, for your kind feedback! I´m glad you enjoyed the poem.

This part of the story has a happy ending, but what follows is not so nice. Theseus runs away with Ariadne, but then cruelly leaves her deserted on the Island of Naxos. There is a famous opera about her sojourn there.

Later, the god Dionysos falls in love with Ariadne, takes her as his wife, and she undergoes apotheosis to become a goddess herself.

Yes, Theseus turns out to be rather a cad in some ways– a flawed hero, like all the heroes of the ancient pagan mythology. He saves his fellow countrymen, but then ditches his wife, and drives his own father to commit suicide when he forgets to switch the flag on his returning ship from black to white, to indicate his victory over the Minotaur. The father, seeing the black flag and thinking that he has lost his son, throws himself off the castle tower in despair. In the longer poem from which this is an extract, I mention these failures on Theseus´ part and end the poem by pointing out how the flawed heroes of ancient mythology bear witness to the human longing for a perfect hero, free of flaws. Echoing the theory of C.S. Lewis about how ancient myths foreshadowed in some ways the Christian meta-narrative, I point how this longing for a perfect hero points to and is fulfilled in that One greater than Theseus who, free of all flaws, faced down an even greater foe than the Minotaur and won and even greater victory.

The early Greek Christians thought the same about the Titan Prometheus, who had created mankind, brought them fire, taught them arts and protected them, and finally was chained and nailed to a mountain as a punishment for loving the human race so much, and being a rival to Zeus. It was easy to see Prometheus as a prefigurement of Christ, especially as his nailing could be construed as a kind of crucifixion of mankind’s Great Benefactor.