Gilgamesh Lines

Introduction

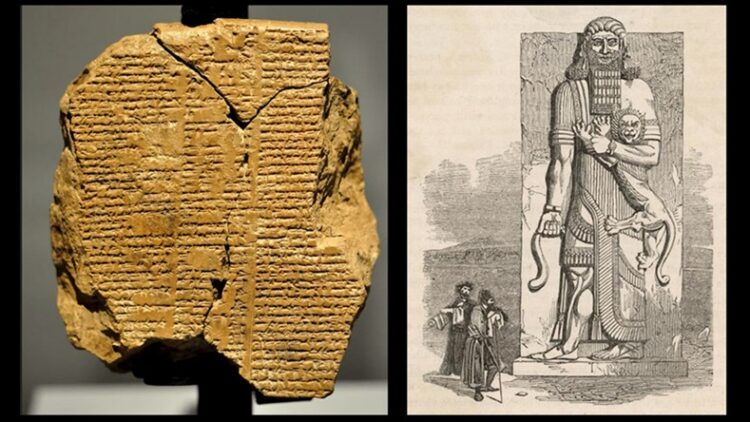

In 2011 when we were evacuating Iraq, looted antiquities entered the market. One such was this shard which features 20 partial lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh, likely inscribed before the seventh century B.C.

Verse translation “I” occurs early in the epic. Verse translation “II” occurs slightly farther on. Together the translations bracket a notion of civilization, “wildness and taming.”

Because incomplete, because versions of Gilgamesh differ in particulars, and because cuneiform writing allows broad, sometimes divergent interpretations, there is not a single definitive version of the epic. Then too, this recent Kurdistan text (Neo-Babylonian) follows the more ancient texts from Uruk (Late Babylonian) and Ninevah (Assyrian).

Three characters worth noting: The anthropomorphic giant, Humbaba, spawns the forest “demon-trees” that he rules and guards; Enkidu is an anthropomorphic man, companion friend of Gilgamesh; Gilgamesh is Sumerian, possibly an actual king of Uruk (2900–2350 B.C.) whose legends are recorded in five surviving cuneiform documents that together form the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Between these translated episodes, Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the Bull of Heaven. Enkidu for his part in the slaying is condemned to death. Because Gilgamesh witnesses his friend’s mortality, he unsuccessfully seeks immortality and is resigned to death, and that’s the span of the epic.

I’ve inserted two details which resolve the translations into a poetic whole. Enkidu is inserted into “I” and Enkidu’s physical characteristics are inserted into “II.”

I.

A bird begins to sing and soon

Answers echo through the forest,

Some in and others out of tune

Join the merry dinning chorus.

A pigeon moans, a wood dove coos,

A cricket crickets on a leaf,

A stork exults, a booby boos,

Monkey youngsters at mothers shriek.

The cedars sway in Lebanon,

The drummers drum and horns hurrah,

A weary Enkidu does yawn

Before the mass of great Humbaba.

II.

Bull tailed Enkidu opened his man-mouth

To speak these words to Gilgamesh, “My friend,

We have reduced the fertile forest to

Wasteland. How to tell Enlil in Nippur

That hero-like you slew his guardian.

My friend, what was that all-consuming wrath

That trampled down the trembling forest?”

Michael Curtis is an architect, sculptor, painter, historian, and poet, who is currently Artist-in-Residence at the Common Sense Society. He has taught and lectured at universities, colleges, and museums, including The Institute of Classical Architecture, The National Gallery of Art, et cetera; his pictures and statues are housed in over four hundred private and public collections, including The Library of Congress, The Supreme Court, et alibi; his verse has been published in over thirty journals; his work in the visual arts can be found at TheClassicalArtist.com, his essays at TheStudioBooks.com, and his architecture can be found at TheBeautifulHome.org.

What a fantastic fragment. The details about the animal sounds are very charming. I believe this same forest of cedars was also used to build Solomon’s Temple, which makes it perhaps the most distinguished forest in literary history? Well done, Michael!