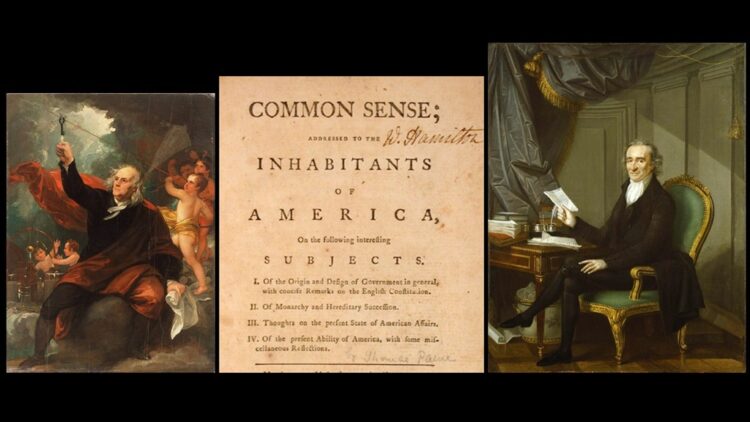

Thomas Paine Publishes Common Sense

London, 1774

A man walked through the door, escaping rain.

His shoes were full of holes where water trailed.

“Beg pardon, sir, the name is Thomas Paine.

I need some work.” He held an ad Ben nailed.

His concave abdomen, curtailed

In thickness, growled, an animal in want

Of some frontier to hunt on. Ben exhaled.

“Why should I hire you?” he said. The gaunt,

Numb Paine replied, “I’ve had a lot of jobs.”

Ben: “List them, then. I don’t pay salaries to slobs.”

He’d been a tax collector. He got fired.

The reason? Well, he couldn’t stomach greed.

Before that he tried sailing. He retired.

What for? His belly was the seasick breed.

Stay-making made him dream—Ben bulged: “Of midlines freed?”

Tom bowed. Ben said, “You’ve disemboweled each trade.

Without a skill set, hunger will succeed.”

Tom fingered pocket pits, shoe-gazed. Dismayed,

He raised his head. His eyes met Ben’s, intense:

“The only skill I have is common sense.”

Philadelphia, 10 January 1776

A man walked through a door, escaping snow.

His finely cobbled shoes were capped with white.

“Beg pardon sir, I’ve got some work to show

You—if you’re not too busy? I can wait.”

A pair of double spectacles stared back

At the brass buttons on a fitted frock.

A scenthound smelling game ahead of the pack,

Ben Franklin sniffed around him, taking stock:

“You’ve something for me—news? Some verse? A headline?

Let’s see it, man! The Penn Gazette has got a deadline!”

It wasn’t news—though that could be exchanged.

The reason? Well, it steps on lots of toes.

It wasn’t verse, though that could be arranged—

Unless the readers will pay more for prose?

It’s not some Busy-Body’s rumor train—

But why no pseudonym? Protects the author.

“I’m not concerned with that.” —“Well, Mr. Paine,

It sounds like you don’t have a lot to offer.”

Tom raised an arm. His eyes met Ben’s, intense,

As he plopped a manuscript. It’s title: Common Sense.

A habit of not thinking something wrong

Will make it appear right, if pondered long.

Defense of custom changes with the season:

Time reaps more converts than unyielding reason.

True Rights are something no one can usurp—

Whether by monarch, Parliament, or twerp.

When hands pervert the pendulum of power

Alarms will sound on faces by the hour.

America, the cause of all mankind,

Is the concern of every conscience that can mind.

Ben clapped Tom’s shoulder. “Marvelous—well said!

This has some first-rate quotes. They even rhyme!

(I turned your prose to couplets in my head.)

Okay, let’s get to work—there’s little time!”

Paine helped get the electric press in sync:

He gathered letters, filled composing sticks,

Set galleys, dampened paper, applied ink.

Ben didn’t need to teach him how to fix

It up. He hooked it to a Leyden Jar

And pulled the lever. Thunder pealed from afar.

“Let’s go!” said Ben. His golden eyeballs glared

And flashed—two stars gone supernova—as

His follicles shot upwards, solar-flared.

His head, white-hot: a surface of such frazz

And dazz that Paine was blinded. Then a bolt

Of lightning came cascading down and struck

The rod on Franklin’s shop. Charged with volts,

The press smashed ink to paper that was sucked

Outside by wind, dispersing through the city,

Falling on residents: a boy, a maid, a kitty.

Ben shook his head. “We need more power. Your

Pamphlet deserves a widespread circulation

Throughout the colonies—let’s make it soar!

We just need some reliable flotation.”

Paine scrunched his brow: “You really think that’s feasible?”

—“Where is your ‘can do’ attitude? Don’t naysay!

Let’s bundle up. It’s cold—our buns are freezable.”

Ben saw some children relishing a playday

Outside, all frolicking upon some heights

Nearby. A lightbulb flickered—they were flying kites.

“Hey kids—mind if I borrow those?” —“Ah shucks,

Mister …” They shrank—until he passed out wads

Of Benjamins: “Here—have a hundred bucks!”

Paine took a bill and read the Latin words

Above the pyramid and the strange eye:

“Annuit cœptis? —Now you’re playing God

By minting your own face? They’ll hang you high!

I’m not sure what’s worse—vanity or fraud.”

Ben shrugged: “You need new shoes? Here—buy some more.

It’s only counterfeiting till we win the war!”

Ben bundled twenty kitestrings in his fist,

Took out a key, and looped them through the bow.

A gust of wind and snow propelled him fast

Upwards as Thomas grabbed his legs, a stow-

away into the heavens. “Don’t look down!”

Ben shouted. Paine’s eyes darted downward, popping.

He saw the speck that used to be their town

And clutched his mentor tighter, as bird droppings

Came raining round them, hitting several pamphlets

That floated with them, high above the dotted hamlets.

Just like that magical nanny, Mary Poppins,

Whose black umbrella took her to the sky,

Avoiding—somehow—eagles, ospreys, robins,

And supersonic engines roaring by

(Today, Big Blue’s no friend to umbreliftics),

So Ben rose higher, higher—higher still!—

Propelled this way and that by kitodriftics.

A grammar maven might describe the thrill

As supercalifragilisticexpi-

yadayadayada. I would call it ‘sexy.’

Our flying fat man made the ladies swoon

Below, fainting into their husbands’ arms

As the wind blew his shirt up and he mooned

Them with his belly. Women loved Ben’s charms!

The fairer sex is looking out for promises

Of plenty—yes, they want the Friar Tucks!

They’re not so hot for matchstick-thin Adonises.

Give them Falstaff—a size that screams ‘deluxe!’—

Or Henry the Eighth! (As brushed writ large by Holbein).

No athletes pimping, preening—plump ones from the coal mine.

Plop—a dropping. A mess on Franklin’s shirt.

Well, now we know why Poppins used umbrellas.

It wasn’t just to complement her skirt—

Or could there be another reason, fellas?

Anyhoo, into the cumulonimbus

Clouds our authors flew: beyond the Alps,

Beyond those deities who zoom to Olympus,

Beyond the sight of curious, craning scalps.

Paine looked above him, seeing (“Not again!”)

That golden crackle in the eyes of Lightning Ben.

The storm clouds covered Thomas—a black cloak.

Inside his windblown ear, thunder was mingling.

Holding the kites with one hand, Franklin croaked:

“Have no fear, Thomas. You may feel some tingling,

But don’t let go!” —Then lightning struck and shook

Ben’s body, glowing luminescent yellow,

His fat absorbing the electric shock—

Mostly. Below, Paine’s limbs all turned to Jello;

Complexion, lightened (the charge popped a pimple).

And that’s how they defeated death. It’s just that simple.

With Franklin’s free hand, he began conducting.

Far, far below, the press was smashing script

Inside the printing shop. The wind, abducting

The papers, sent them swirling upwards, shipped

To the empyrean—an inky vortex

That Ben batoned along the Eastern Seaboard

To be impressed in every frontal cortex,

His fingers dancing on an unseen keyboard.

Notions, like notes, can echo in the ear,

Each phrase crescendoing on themes of hope and fear.

Right down the street, a woman sat in mourning.

Her husband, a militiaman, had died

When a stock of powder blew up without warning.

Sighing, she hugged her plain white shawl and tried

To read the Bible as her children played.

Just then, a pamphlet blew in from the window.

The eldest listened; young attentions strayed:

Digging a grave turns dreamers into widows.

Raising a flag will hoist the hopes of kiddos.

She picked a needle, pricking. Finer than a spade.

Nearby (in Philly still), Jefferson’s quill

meandered: wife, remote; mind, overloaded.

Ideas floated here and there at will

Like feathers from a mattress that exploded.

A social contract called—but how to label?

And then a pamphlet landed on his table:

“To have and hold”: what tender lover meant

To cherish an abusive government?

Jefferson stroked his plume and wet his nib.

With common sense spit up, he’d need to fix a bib.

Up in the Berkshire mountains, a man sworn

To carry out a hopeless quest could swear,

While squinting through an unrelenting storm,

That he heard a voice, carried upon the air:

Give up! … Go back! His head and footsteps wandered.

And then a pamphlet struck his face. He pondered:

Importing goods will kill a man through taxes;

Surmounting vices, when a man relaxes.

Exhausted, Henry Knox’s head felt soft.

He pulled it from the clouds and, hardened, trudged aloft.

Across the Appalachians, hunters sat

Around a fire they had named in praise

Of Lexington and Concord. Now they pat

Their grumbling stomachs, groaning as they gazed

Into faint embers, lost in wild Kentucky.

And then a pamphlet blew in overhead.

One hunter bit an edge to taste it (yucky).

Survivors have no need to please the dead:

An empty belly has no room for pride.

Nodding, men skewered leather boots, which they then fried.

In Cambridge, soldiers gathered to complain.

Some annual enlistments were expiring.

“Where’s our wages?” — “What we have to gain?”

“Why should we stay?” The men were all inquiring.

They turned to leave: “I’m off to see my mum!”

They bolstered cowardice with righteous chattering:

“You call this ‘freedom’—marching to a drum?”

Washington, mounted, tried to halt their scattering.

He scowled, erect—the ‘statue method,’ hollow.

He turned to speech—his oratory, hard to swallow:

“A little longer, men—we’ve almost won!”

(Nope—but it’s not a lie if you believe it.)

“Immortal honor’s lost to those who run.”

(Yes—but who cares? The living don’t achieve it.)

“For liberty, men suffer countless trials.”

(Truisms all depend on your perspective.)

“Brothers-in-arms, you’ve marched so many miles!”

(Appealing to experience is effective.)

Feet fled—numb soles, they couldn’t toe the line.

Then pamphlets started raining down. Was it a sign?

One by one, shoes stepped on papers, stooping.

The poisoned mind believes its born to reign.

One by one, their faces fell, eyes drooping.

Why should an island govern distant plains?

One by one, their mouths were filled with quotes.

The powers that subdue us won’t defend us.

One by one, their feet declared their votes.

Though freedom’s far, the future will commend us.

The soldiers all told Washington they’d stay—

But not from loyalty. For common sense. (And pay.)

The overeducated in New York

Were starting to mistrust their vain abstractions.

Some squatting Marylanders, out of work,

Perceived that sloth produced dissatisfaction.

In Mass. the Puritans, en masse, were drinking

Small glasses, lifting prohibition’s ban.

The Georgia Peaches, sipping tea, were thinking

That abolition was God’s rightful plan.

All through America, fools turned to wise men,

Equipped with Thomas Paine’s good judgment to advise them.

Poet’s Note: The first of these excerpts appears in Volume 2, Chapter 5, of the mock-epic Legends of Liberty. The second is from Chapter 15 of the forthcoming volume.

Andrew Benson Brown‘s epic-in-progress, Legends of Liberty, chronicles the major events of the American Revolution. He writes history articles for American Essence magazine and resides in Missouri. Watch his Classical Poets Live videos here.

Wow! Absolutely epic, Andrew! Great work.

You have a true gift for both narrative poetry and humor. I think your narratives of the Founding Fathers are quintessentially American and contemporary. You retell our foundational myths in verse, but add a very (dare I say?) postmodern flash with your dry wit and contemporary references (e.g. Mary Poppins and Jello — the latter as an end-rhyme, no less). The epic simile (though used as more of a metaphor) of birds pooping was particularly inspired.