Practicing Brahms

—Piano Solo, Intermezzo, Op 118 No. 2 (1893)

My Steinway’s gelid laquered keys turn gauzy.

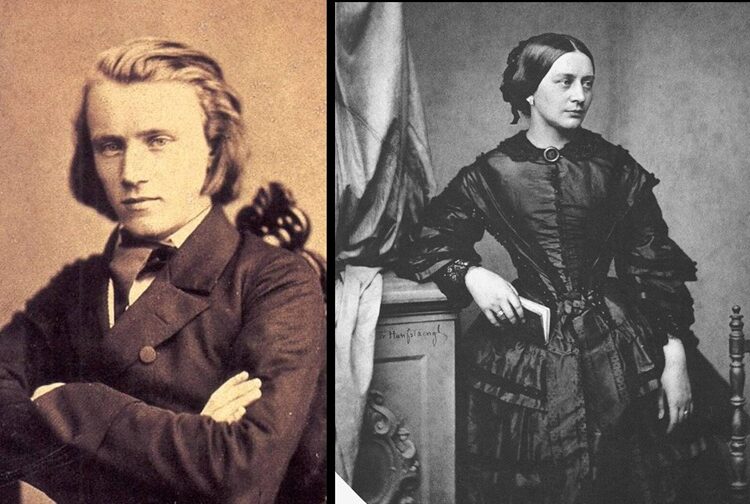

The notes and markings that Johannes wrote

(composed with goose-wing feather quills) now float

aloft in realms of lush melodic poesy—

pining for Clara, forty fervid years

la belle dame sans merci—unconsummated.

I pause, caress the keyboard lightly: freighted

with bygone loves, convulsive racking tears.

Mary Jane Myers resides in Springfield, Illinois. She is a retired JD/CPA tax specialist. Her debut short story collection Curious Affairs was published by Paul Dry Books in 2018.

Ms. Myers,

Congratulations on a splendid accomplishment. This is exactly what a poem should be and do.

May you have many more years of such work…and piano practices.

Dear Gerry

Thank you for your kind words. It’s easy to write a poem when the music is a masterpiece!

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

So well articulated. You are blessed with the right words

of appreciation for and the opportunity to spend time with one

of your Muses.

Thank you, JD. I am blessed with wonderful readers like you.

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

Mary Jane, your poem flows like a Brahms opus on a Steinway.

Thank you Roy. It is indeed a joy to play Brahms, albeit frustrating to fall lamentably short of the standard of world-class pianists like Radu Lupu (already unfortunately not with us, but we have his wonderful recordings).

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

These two perfectly chiselled quatrains are an example of brevity and intensity combined. Because the poem is short, individual words and phrases exude a more powerful force. The Steinway piano’s “gelid, lacquered keys” is one instance of this; the other is the magnificent closure of “convulsive racking tears.”

Joseph

Thank you so much for your kind words. This particular poem is autobiographical, so perhaps I unconsciously poured instinctual emotional intensity onto the blank page.

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

This octave of paired quatrains describes and explains both the sound effects of piano practice, and the emotion carried by this particular Brahms piece. You use words that imply musical lightness in contrast to the hard shiny surfaces of the material piano: gauzy, feather, float aloft, pause (after which the comma itself is airy), caress the keyboard lightly.

I notice you choose envelope quatrains, closed (abba cddc) to allow the first to contain the name Johannes, and the second the name Clara. And they stand opposed in masculine and feminine rhyme (fmmf, mffm). Moreover, the word “poesy” that ends the first quatrain, though it could be pronounced po-eh-zee, must be a “posy” to rhyme with “gauzy.” Thus Johannes concludes his part of the poem by offering a flower to Clara.

The second quatrain ends with tears, but at this moment in time one can only imagine whether they belong to either or both of the bygone lovers, or to the present pianist.

“Gauzy” rhymes neither with “posy” nor “poesy.” If Brahms is offering a flower to the long-dead Clara Schumann, there is no verbal evidence of it in this poem.

You are indulging, Margaret, in a fictive mimesis of literary criticism.

It’s an IMPERFECT RHYME. Mary Jane knows that.

I’m sure she does. I know it too. That still doesn’t mean that Brahms was giving a flower to Clara. That’s what was fictive in your criticism.

Probably the most fictive element in the poem is the “belle dame sans merci” cliche applied to Clara. She and Brahms were in frequent contact throughout their careers; Clara was a supporter, performer, and occasionally forthright critic of Brahms (case in point: his 1st Symphony), much as were Brahms and the violinist Joachim (not to deny the mutual romantic attraction of Brahms and Clara, which may have begun even before Robert’s permanent commitment to the asylum at Endenich; nor an extended estrangement between B and J).

It should probably be noted, Joseph, that you may be writing under a fictive surmise: Brahms published his Op. 118, with a dedication to Clara, three years before his death–less than a year after Clara’s.

Thank you for the clarification, Julian. I still think that the use of the word “poesy” cannot be reasonably understood as an allusion to a flower.

Dear Julian

I appreciate so much your erudition with regard to Johannes/Clara. I hesitated a lot over that French phrase–but my Google search reassured me that some scholars so denote the relationship, because the “longing” was more on Brahms’s side, and it’s thought she never agreed to a sexual connection. (Could that remark simply be an AI summary?–but close enough for poetic work!) I liked the phrase because it so “resonates” with Romanticism (I was thinking of Keats). By the 1890’s, composers had “moved on”–but not Brahms–he composed (with goose quill pen) those lush melodies to his dying breath.

An aside: another aspect to their relationship: Clara was 14 years older. Apparently, Johannes years later developed deep longings for Clara’s daughter. I’m reminded of that strange Thomas Hardy novel “A Pair of Blue Eyes.”

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

Dear Margaret

Thank you for your close reading of my poem and your kind comments.

I deliberately constructed the fmmf/ mffm pattern, but I didn’t realize I had separated the two names, which seems to add a subtle effect. I owe a thank you to that invisible muse who is so helpful.

It is a particular challenge to play “soft” pieces on a grand piano. My amateur tendency is to “strike at” the top notes, which creates an unsettling and jarring effect. That is, those gelid keys do not turn nearly gauzy enough!

And yes, somehow the personality of a composer seems to “intermingle” with the performer’s own immediate present. That is, while playing Haydn, somehow the spirit of of the Hungarian Versailles seems to inhabit the room. With Brahms, the performer somehow feels part of a fictive liebestraum: imagining, say, Elizabeth Barrett, eloping to Italy with Browning in the dead of night!

I’m intrigued by the wordplay of the word “poesy” and “posy.” Again, your comment is interesting to me, as I hadn’t considered the idea. In the Merriam Webster unabridged dictionary, “posy” originally was an alteration (contraction) of the word “poesy” and meant a brief sentiment, often inscribed in a ring. Brahms was a musical composer, and I suppose we could think of this 6-minute solo piano piece as a “brief sentiment.” This usage is not yet labeled as obsolete, though I think in contemporary American usage, everyone defines posy only as a small flower arrangement. Aren’t words fascinating?

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

Mary Jane, you have managed to keenly express so much feeling, profundity, and beauty in just eight lines… very fine work!!

Theresa

Thank you so much for your kind comments. It’s wonderful to have skilled poet-colleagues as appreciative readers.

Most sincerely

Mary Jane