The Last Caesar

—Ravenna, 476 AD

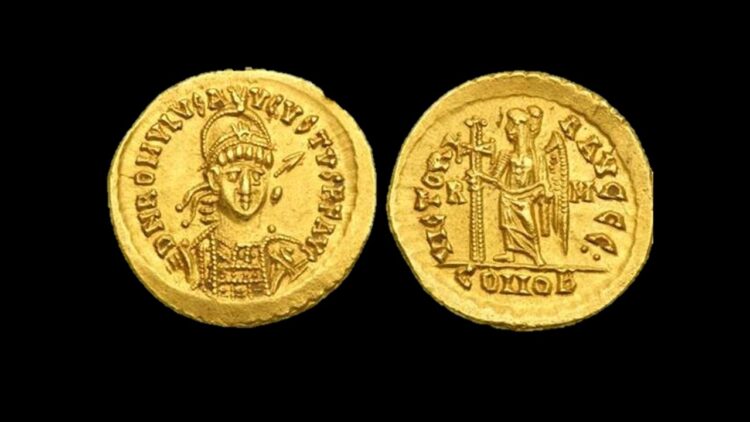

The figure on this golden solidus:

a beardless boy, his dress a bossed cuirass,

helmet adorned with Rome’s imperial crown,

Augustulus, Orestes’ handsome son.

The annals say: Rome weakens year by year,

Byzant holds strong; Hesperia quakes in fear.

Attila’s soldiers start to infiltrate

the Senate’s armies. Soon they penetrate

the topmost ranks. Orestes grabs command,

pesters the Senate to give cash and land

so alien troops might settle down in ease.

The treasury lacks the lucre to appease

barbarians primed to burn and hack and hew;

these thugs are many, citizens too few.

Orestes takes Ravenna’s palace, drapes

the purple cloak around his son who apes

with extroverted glee imperial pomp,

delighting in a whirl of ceaseless romp.

Within a year a bold barbarian,

Odoacer from the Scyrri clan,

murders Orestes, storms Ravenna’s gate.

The giddy teen is forced to abdicate.

That German must have gazed at him in awe:

exquisite face, lithe body without flaw.

Such brutal warriors typically behead

all rivals, without quarter. He instead

delays. How splendid if this youth could be

his private plaything, soused in revelry.

But fierce tribes practiced stoic discipline.

No time for larks; their focus was to win.

Odoacer forced the Senate to reject

Augustulus, and further to accept

Constantinople’s Zeno as the sole

potentate. Hence his consequential role,

ordained to topple power in the West—

this edict more explicit than the rest.

The feckless boy retired to Naples Bay,

a villa where divertissements held sway.

A life all annalists would overlook,

except his name is listed in the book

of Western emperors. He was the last

so diademed; Rome’s fatal die was cast.

Mary Jane Myers resides in Springfield, Illinois. She is a retired JD/CPA tax specialist. Her debut short story collection Curious Affairs was published by Paul Dry Books in 2018.

While this is an impressive historical reflection, Mary Jane, you’ve found the story of a boy in it. I come away with both in mind. History can pass from grand to trivial to missing in action, but the process takes a bit of time rarely so well touched in lyric as you do here. Part of that is the few pictures of the “Last Caesar.” Interesting to remember that the name carries on today, with many a Cesar and Cesare, and with titles such as kaiser and czar into the century recently past. Your fleeting farewell to Augustulus poignantly recalls that single important-for-a-moment person about whom there is something to remember, but not much. The reader is carried back, as well, to Augustus and the great family’s entry into Roman lore a little earlier. Many layers here, and a few more that are also distant from us in time, with the first “barbarian” ruler of Italy, Odoacer of the difficult name. I’ve heard it pronounced by Americans and British, and your two lines including him sound still different. That’s intriguing; I like the effect of uncouthness.

Your presentation is a sort of “annal reading,” capable of conveying plenty of information without an intrusive speaker. It also subtly defines the emotion of the whole. We glimpse the past as a period over and done with, no warnings and no regrets except those we choose to take. And those are likely to focus on the larger classical culture long gone–if not on these persons who disappeared even more swiftly into time. This is a thoughtful poem of many and varied angles of vision.

Margaret

Thank you so much for your nuanced reading of my poem. I was experimenting with “form”–and I followed closely two master poets. Browning’s “Protus” (Revised 1863 first published 1855) is a multilayered poem–in rhymed heroic couplets–the narrator is in a museum, and is comparing busts of Roman emperors with their histories in the annals–and he describes the particularly ineffective “Protus” (who is a fictional character invented by Browning). I also studied “Orophernes” by Cavafy (1917)–where the narrator is studying the image on a four drachma coin of a “lost boy ruler” (there are many such in Hellenistic times–a period with which Cavafy was obsessed). I found a scholarly article that Cavafy may have been influenced by the Browning poem. In any event, I think the idea works well–though I’m not nearly at the level of these two accomplished master poets.

I focused in particular on Augustulus because he is considered (at least by earlier scholars) as the “last Roman emperor”–more recent scholarship has challenged that simplistic view. It’s sobering always to reflect on the rise and fall of empires, which in many cases, to steal Eliot’s line, end not with a bang but a whimper. These empires seem to waste away, almost as if they are killed by some virulent slow-acting bacillus.

Re: names: I researched the pronunciation of all five names: and found differing pronunciations for four of them “Zeno” seems to have an agreed-upon pronunciation). So that gives the poet perhaps more “license” when trying to construct iambs!

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

Mary Jane, extremely impressive well-written historical lesson with a depth of knowledge and use of erudite words that stimulate the senses. Those of us who have extensive graduate history courses and have read “The Fall of the Roman Empire” extend these lessons to the present time and remonstrate against the invasion and acceptance of legions of illegal immigrants who do not share the cultural and religious values of our nation.

Mary Jane, to be more precise, I referenced “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon. My grandfather gave me the book when I was in high school.

Roy

Thank you for your kind comments. I have taken very few “formal” history classes. That said, I like to read! As a twenty-something, I read an abridged version of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall. Then, about six years ago, I read and discussed this work with a Zoom “Great Books” book group. They were reading the abridged together–but I plowed through all six volumes of the unabridged, “just because.” I became fascinated almost as much by Gibbon himself as by his history of Rome. What an interesting mind. So often our intellectual trail-blazers are auto-didacts.

In constructing this poem, I consulted Gibbon’s pages on Augustulus. That said, I’m aware that modern scholars have more available information, and that this time period is complex. I visited Ravenna when “backpacking through Italy” in my twenties. A few years ago, I read Judith Herrin’s excellent history of Ravenna (published in 2020). She is a careful scholar. I didn’t have this book available when writing my poem. That may be a blessing, because sometimes with “too many details” a poet can get overwhelmed and give up!

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

An interesting historical poem about a figure concerning whom little is known, except for a few scraps of information. It should be noted that on the gold coin with his image, the title and name “Caesar” appears nowhere. In place of the normal letter”C” for CAESAR, the coin has “DN” before the name ROMULUS. This stands for “D[ominus] N[oster] (our lord). And the expected IMP (for emperor) is missing. Even in his own coinage Romulus Augustulus was a shady claimant to imperial rule.

Odoacer spared the kid because he was hardly a threat to the Germanic takeover. No money, no legions, no political allies, no significant influence outside of Ravenna, and totally unresisting. So Odoacer pensioned him and his family off to a fortress near Naples, where he spent the rest of his life and was heard of no more.

Joseph

Thank you for your kind comments. I don’t know much about Roman coins–and I’m grateful to you for pointing out this fascinating information. In fact, I possibly could expand this poem by a few lines to reference these facts.

My brother dabbles a bit in ancient coins–though he’s not a serious collector. In researching this poem, I came across several websites where ancient Roman coins are traded. A whole world out there! I also have come across “ancient coin hoards” in various museums–but I typically don’t linger long before those glass cases. I like to spend time looking carefully at mosaic floors and marble statues!

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

This is a skilfully written piece of historical narrative, Mary Jane. Romulus Augustulus was not, I think, universally accepted as Roman Emperor and his predecessor Julius Nepos was still alive and never recognised the boy upstart. Nevertheless, Romulus Augustulus stands as a strange historical footnote at the end of the Western Empire. He is remarkable as a former emperor who was simply never heard of again. There is no involvement in subsequent politics, there are no efforts to regain his position or any role at court, there is no place or date of death and he has no known descendents. He descends into complete and immediate obscurity. Your poem very neatly captures his inconsequentiality, that of a boy not even fit to be a “private plaything, soused in revelry.” You capture the futile frivolity of his proclamation as emperor very well indeed.

Morrison

Thank you for your kind and perceptive comments. A very mysterious figure, indeed. His scarcely-remarked life and inconsequential reign lead naturally into ruminations about the ironies of history, and to melancholy reflections about the decay of mighty empires. “Footnotes” in many ways are more interesting, at least to poets!, than to the “wide-screen action” of “kings and queens” or famous military battles or spectacular assassinations.

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

While a great recitation of the history, the poem often comes across as stiff and relies heavily on historical jargon. If your intention was to create a historical account of events then that is fine, but it does not capture any emotion or strong imagery. Why should the reader care about the final emperor? Should we care? I found that you got too stuck into the history of it all.

To Christian Muller:

Several persons have already commented favorably on Ms Myers’ poem, so it would seem that there are some readers who care about the subject and who are pleased by the poetry. Do their opinions not matter?

When you ask “Why should the reader care about the final emperor?” you are really just saying this: “I don’t find the poem interesting or important.” That’s just a repetition of the old critical cliche from the 1960s, which dismissed poems for “not being relevant.”

Any subject can be treated in poetry, and the poet is under no obligation to compose in a certain way. Persons who say that they “don’t care” about a particular poem are usually agenda-driven types who only want to see poems that support their viewpoints.

Christian

Thank you for your careful reading of my poem, and your helpful comments. You are spot-on: there is not much “emotion” in this poem. My intent was to make a “philosophical point” about the end of an empire. One of my favorite poets is Constantine Cavafy. He muses philosophically about the melancholy end of Greek power during Hellenistic times yet also manages to make the reader very sad for the individuals who were caught up in the decline and chaos. You might enjoy a poem like ” Orophernes” where Cavafy describes the fate of a boy-ruler whose face is on an ancient drachma coin. The reader definitely feels compassion for that boy.

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

I have to comment: I am a big fan of Cavafy, too. I love the intimate, dreamlike melancholic atmosphere he creates. Reading him feels as though I’m a privilege guest in his inner world.

You condense earthshaking events into a short, almost dreamy narrative — no dialogue, just description. Your exposition renders the setting immediately relevant. Infiltration, appeasement — the message is not lost. Your placement of the youth in the narrative reflects his role, more of a bystander to the events surrounding him, so inconsequential that historians do not bother to record what happened to him (as you satisfyingly note).

I also appreciate your mentioning of Zeno. Odoacer’s coup was seen as a transfer of authority back to a single emperor, so when the Western Empire fell, no one at the time would have recognized it as such. In fact, Zeno was reluctant to acknowledge Odoacer’s coup because the emperor he had appointed in the West earlier – Julius Nepos – still lived and claimed imperial authority in Dalmatia.

Zeno himself was an interesting character, too. From Isauria, he was regarded as something of a rube, so he adopted the Greek name Zeno to appear sophisticated. Odoacer supported a failed rebellion against Zeno, so in retaliation Zeno promised Odoacer’s titles to King Theodoric of the Ostrogoths if Theodoric could conquer Italy. Of course Theodoric did and killed Odoacer, only for Justinian to invade Italy and put an end to the Ostrogothic kingdom fifty-odd years later. Chaotic times. But enough of my tangent…

Adam

Thank you for your kind words. Isn’t history fascinating? Judith Herrin’s scholarly book on the history of Ravenna (2022) explains well the complexity of the political realignments of the Roman Empire in the late 5th century.

I recently read the new Cavafy biography by Jusdanis/Jeffreys. I was somewhat disappointed–too much “armchair psychologizing” for my taste. 12 years ago I visited Cavafy’s apartment in Alexandria. Quite a wonderful memory–our Coptic guide couldn’t find the place easily!

Most sincerely

Mary Jane

At school the fall of Rome was barely touched on. All I came away with was that the Vandals and Goths did her in, hence the word ‘vandal’ for a mindless destroyer. As for Goths, the black clad, angsty teenager (from the association with Medieval Gothic architecture and Gothic Literature) had not been invented back then.

Thanks for both a poem and an education, MJ.