Timeless

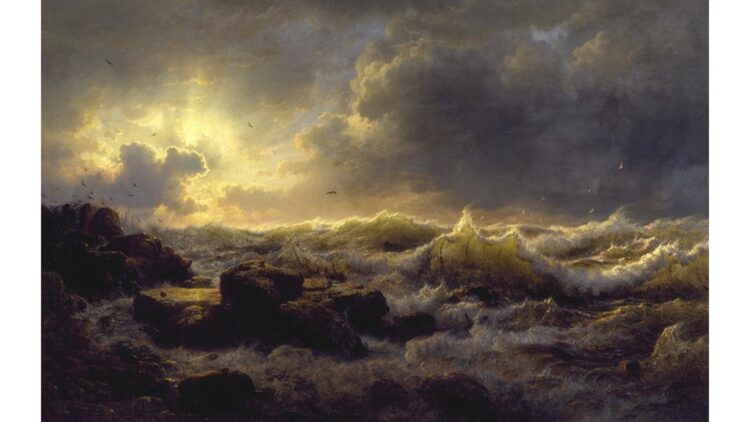

The timeless, gentle swish of wave-washed sand;

The echoed “chock” of rounded wave-washed stone;

The silent, skittered feet of pipers and

A distant sea-tossed crab boat’s throbbing drone.

The squawk of gull, the sharp-shrill caw of crow;

The unseen shaft of air where eagle’s soar;

The dance of dune grass in the breeze below,

The cloud-cast sky; my walk along the shore.

With cane, commode and walker near at hand

I lie abed, by age and pain entombed.

A lubber on a mattressed speck of land;

Cut off from what was once my life, marooned.

My daily stroll now but a memory.

Yet in the night I dream I hear the sea.

James A. Tweedie is a retired pastor living in Long Beach, Washington. He has written and published six novels, one collection of short stories, and four collections of poetry including Sidekicks, Mostly Sonnets, and Laughing Matters, all with Dunecrest Press. His poems have been published nationally and internationally in both print and online media. He was honored with being chosen as the winner of the 2021 SCP International Poetry Competition.

James, I am deeply moved by your poignant poem on aging and our connection to the natural world. And I’m reminded of Santiago, in The Old Man and the Sea, who dreamed of his younger years when sailing along the African coast, observing the lions. I believe your poem should stand the test of time.

I love the musicality of this poem, especially in the first two quatrains: I can hear the sounds you describe as I read. The rest of the sonnet is sadly moving.

I must say, James, that this sonnet was richer in images than the best muffin I ever ate was in blueberries. You move through a cascade of natural images and finally land on yourself embedded in the seascape. After that, things go downhill — not for the poem itself, but for the subject living its narrative. I trust that this is not the author’s actual current enfeebled state, and so I view the closing lines as a premonition of the inevitable. Life is bittersweet.

A very beautiful and very skilful poem; there is much to admire in this but one simple thing I think outstanding: the use of rhyme and enjambment in the lines: “The silent, skittered feet of pipers and

A distant sea-tossed”

The run-on/rhyme of ‘and’ here is brilliant as it mimetically recreates that sense of timelessness, or its synonym endlessness: for what is the opposite of enjambment? The end-stopped line, which by circumventing – and yet rhyming at the same time on such a seemingly trivial word – creates a wonderful, ‘endless’ flow. This is poetry of a very high order.

The move from octave to sestet offers a shattering contrast, skilfully achieved and of great poignancy. Not cheerful, but sobering. It reminds me to get off my backside and make the short trip to the coast while I’m able. I’ll do so tomorrow. Thank you, James.

James, this was so profound and touching in its melancholy memories of another time long past. I particularly was taken with the word “chock” that was perfect for the waves crashing on the shore.

Beautiful! The abrupt mood shift reminded me of the scary images sent by the ghost of Christmas future in A Christmas Carol. I hope they are but shadows that can be changed. Even still, the last line is very comforting.

Lovely final couplet. Great job on the sonnet with its Volta as well as the use of rhyme and alliteration.

I must agree with James Sale that “Timeless” is poetry of a very high order. That begins with the elegant metrics and parallel structure and descriptive mastery of the sonnet octave, itself paralleled with the sestet’s contrasting point of view. Let me also focus on the line Sale selected for praise of enjambment, to point out the very small touch of the rhyme word “and” supplying the full name of the bird there described, the sandpiper. As spoken, of course, the sound of the line ending would be “PIE purz AND,” and thus a technically perfect rhyme for “sand” two lines above, because preceding consonants differ. This is a tiny note indeed, a strictly unnecessary perfection that James Tweedie could well have performed naturally with little or no thought of it. There are many more notable timeless beauties here!

A very moving poem, the sort I would have liked to have known (for both our sakes) when my father was bedridden and I was staying with him.

The beach-side sound and sight imagery builds up a wonderful picture, only for us to discover that the narrator can only experience this in memory. This is followed by some more nautical language of the ‘marooned’ narrator who is ‘A lubber on a mattressed speck of land’ – what an image!

An interesting ending, with nostalgia perhaps colouring that feeling of helplessness.

I thought this was a brilliant, bar-raising sonnet. You certainly got my attention, James.

I would like to assure you all that i am in relatively fine fettle and not, as of yet, lubbered abed!

The poem recalls my grandfather’s final convalescence where he daily cried out for someone to drive him the two hours it would take for him to see his beloved Lake Tahoe one final time. He never got there but I imagine he dreamed of it in detail as he relived it all in memory.

If I captured some of that then satis est.

Thank you all for the affirming comments.

This is indeed a beautiful and sad poem. The diction is perfect — balanced between monosyllables (for solidity and weight) and disyllables (for movement). The compounds are tightly done: wave-washed, sea-tossed, sharp-shrill, cloud-cast. “Sharp-shrill” is especially striking as an alliteration of consonant clusters.

There’s only one trisyllable (“memory,” in the closing couplet), but then it is followed by the very powerful end line of monosyllables: “Yet in the night I dream I hear the sea.” This finishes the piece with powerful emotional weight.

One metrical question: in the twelfth line, I miss a beat. Would it be fixed by adding the adjective “active” in front of the word “life”?

Oops. I caught that and fixed it before sending the poem to Evan. I must have sent the wrong file! The line should begin with, the words, “Cut off from what was once my life . . .” Good catch, and thanks for the comment.

Fixed, James!

Tyvm

This sonnet stands out to me for two reasons. First, you paint a vivid picture of the seaside scene. I can almost smell the salt and hear the waves crashing against the shore. But this is not an atmospheric piece; the vivid scenery serves as a backdrop for tragedy — the freedom of the sea is contrasted with the decrepit condition of the narrative voice. And yet it ends on a hopeful tone: decrepitude and immobility have not extinguished the inward sense of freedom. My other point is that although you write a Shakespearean form, your ideas follow a Petrarchan flow: the turn definitely appears at the beginning of third quatrain, separating the ideas into an octave and a sestet, even if the rhyme and stanzification follows Shakespearean form.

Adam, I nearly always approach my poetry as telling a story, with a beginning a middle and an end. In a sonnet the end (or turn) sometimes comes at the closing sestet and sometimes at the closing couplet—or—if the story flows elsewhere it could turn up in the middle of somewhere else. It depends. I will leave it for Petrarch, Shakespeare and Milton to decide whether I am one or the other or, more likely, a some sort of hybrid (like my Kia).

James, as a lover of sonnets and a man of advanced age, I was deeply touched by your work. Thank you!