The clerihew is a kind of epigrammatic verse (normally) consisting of a pair of rhyming couplets. The first line will usually introduce the name of a famous person. The following three lines will describe some “fact” about that person which may contain a grain of truth or may simply be utterly outrageous. The verse form is named after its inventor Edmund Clerihew Bentley (1875-1956). The lines to be of uneven length and often the first rhyme will be a humorous one off of the subject’s name.

I.

Archbishop Tutu

Kept in his mitre a hoopoe,

But few zulus knew the ensuing to-do

Was due to the cuckoo that flew up his tutu.

II.

Queen Victoria said “We are not amused”

When mildly accused of being confused.

“We are a queen and therefore excused being lax

With some aspects of pronominal syntax.”

III.

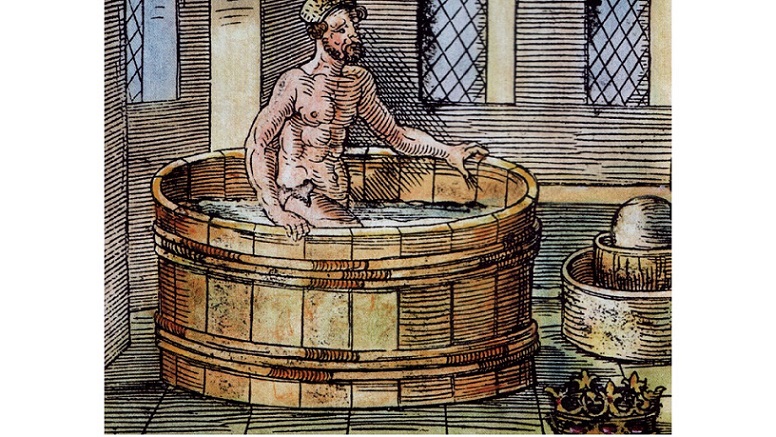

Archimedes of Syracuse,

In his bath he changed a fuse,

And observed that a saline solution

Helped accelerate electrocution.

IV.

Empedocles

Thought it quite a droll wheeze

To leap into Etna’s crater.

Still missing three thousand years later,

Invoking a sense of unease.

V.

Sir Leslie Stephen

Found the Alps so uneven

He renamed the Matterhorn

The Should-Be-Much-Flatterhorn.

VI.

Immanuel Kant

Knew his brain cells were scant

When he started the silly season

With his lightweight “Critique of Pure Reason”.

Peter Hartley is a retired painting restorer. He was born in Liverpool and lives in Manchester, UK.

Ha! Thanks, Peter. A fun way to start the day. As they say, “A Clerihew a day keeps insanity away” . . . or something like that. In any case, as I read through these miniaturesque gems, I couldn’t help but think how formal verse (with rhyme, rhythm and structure) is so much more effective than free verse at conveying humor, satire, whimsy,, etc. I tried to imagine how to translate your Clerihews (or even a simple limerick) into free verse. I gave it up as impossible. Come to think of it, has there been any humorous free verse written since Eliot’s “Book of Practical Cats?”

James, thank you for your comments and observations. The quality I admire most in the original clerihews is their utter pointlessness, and the feeling that he (deliberately) leaves in the reader that he couldn’t really think of anything of any great moment to say, like Sir Christopher Wren “Going to dine with some men” and “George the Third ought never to have occurred”.

Paul Gauguin

Was a disciple of Shogun

He fed only on Gazpacho

And his behaviour turned macho.

Sandro Botticelli

Despised Lime Jelly

But was more at home

With a Derby scone.

Dear Mr. Hartley,

I am writing to ask permission to use your poem “The Dodo of Mauritius” in my new post on Substack.com. The post is titled “The Poetry Zoo,” it appears each Friday, and every week there is one animal poem (sometimes several short ones) along with relevant commentary and illustrations. It is free to all readers, and you may join at: thepoetryzoo.substack.com.

I hope you will say “yes” to my using your poem.

With all good wishes,

Sam Staggs

Dallas, Texas, USA

Salvador Dali

Felt he could be President of Mali

He had the panache

And could twirl his moustache.

Albrecht Durer

Used to read the Torah

Surer than surer

He would have displeased the Fuhrer.

L.S. Lowry

Never visited the Bowery

For his muse was in Lancs.

To which he gave eternal thanks.

Toulouse Lautrec

Was a nervous wreck

It was from being with his fellows

In too many bordellos.

How strange, looking at your first one, as I recently wrote this:

Salvador Dali

On a visit to Bali

Swore in Somali,

Swore more in Bengali

And twirled his moustache in Kigali.

But because it isn’t a clerihew, wrote this instead:

Anthony Trollope

Deserves a great wallop.

His “Barchester Towers”

Goes on for hours.

A few more :

Chaim Soutine

Hated routine

He could paint in a cave

And forget to shave.

Vincent Van Gogh

Was never a toff

He eschewed posh diners

And he worked with miners.

George Seurat

Used to dance the hora

But what really sent him potty

Was doing pictures that were dotty.

Anthony Van Dyck

Once owned a bike

You may think that not much

But wanted to ape the Dutch.

Rene Magritte

Used to live on our street

Often a stroller

He always wore a bowler.

Some of these are amusing, but numbers II and IV don’t fit the bill. The true clerihew has only four lines, and the first is always limited to the name of the person being discussed.

The name in the first line is supposed to set the rhyme for the first two lines:

“George the Third

Ought never to have occurred…”

“Sir Christopher Wren

Said ‘I’m going out with some men…’ ”

Adding a fifth line wrecks the form.

You write, “The first line is always limited to the name of the person being discussed”. I don’t think Edmund Clerihew Bentley would agree with you on that point, and he should know. Just three first lines from the man who gave his name to the verse form: “What I like about Clive”, “The art of Biography”, “On biographic style”. And here is a more modern one; “Did Descartes / Depart / With the thought / ‘Therefore I’m not.'” I’m well aware that two of my contributions contain more than the usual four lines. My Oxford Dictionary of English defines the clerihew as “TYPICALLY in two rhyming couplets”. I’m sure Mr Bentley himself would have extended me the same latitude. Lighten up a bit. Clerihews are meant to be funny. You seldom seem to check your facts before you start pontificating, and I’m not just talking about your attempted arguments with me. But you are beginning to a) get on my nerves and b) give me a persecution complex.

Peter, a form is either a form or it isn’t. I suggested to Joe that he provide a couple of examples of exemplary clerihews. After doing some research, I conclude that Joe is correct in what he says about the clerihew. So:

Peter Hartley,

So unsmartly,

Picked a fight with Joseph S.

Now his life’s a bloody mess.

Perhaps your point would be better made if you gave a couple of examples of exemplary clerihews.

Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Was hardly up to it mentally.

Compared to McGonagall his verse

At best could scarcely be worse.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Was admired for his fine antiquark.

Drinking coffee with his cantatas,

Prattling particle physics with his toccatas.

John Keats

Was known for his scholarly feats,

But on first looking into Chapman’s Homer

“Translation” he thought a misnomer.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Once had a good earner,

Sadly unaware the Fighting Temeraire

Lay toasting on his back-burner.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Painted as though there were no tomorrow,

But much to his sorrow and to his great shame

His three thousand works look exactly the same.

Henry the Eighth

Hans Holbein portrayed in good faith,

That vast corporation with noble restraint

Still took nearly six tons of paint.

Howard of Effingham

Having a baldric he needed a wig

He swore like a trooper and ate like a pig

And behaved like a regular Effingham.

George Frideric Handel

Wouldn’t hold a candle

To Brahms and Liszt

Were he their consultant proctologist.

There was a young man called “Kip”

Who was stung on both ears by a wasp

When they said “Does it hurt?”

He replied “No it doesn’t,

It can sting me all day if it likes”.

You will know “Joe” infinitely better than I do, and he doesn’t know me from a cord of wood I’m relieved to say, but can you tell me is he really that fearsome? He sounds like a world heavyweight boxing champion.

Thank you, Kip.

Just because one man invented something doesn’t mean that his prototype can’t be improved and perfected. We’re all using a helluva better engine than the one constructed by Henry Ford. Those three first lines that Hartley quotes from Bentley clerihews are simply godawful, and I’m glad most modern clerihew writers don’t follow his rotten example.

I didn’t know I was getting under anyone’s skin by simply expressing a viewpoint here. And since I don’t know Peter Hartley from a cord of wood, I certainly haven’t attempted to pick any argument with him.

In any case, let me compose an ad hoc clerihew to address a persistent problem here at the SCP:

Mr. Evan Mantyk

Must be driven nearly frantic

By poets who pay no attention

To propriety, norms, and convention.

Unlike Mr Anderson I am not on familiar first-name terms with Mr/Dr Salemi. Witheringly he tells us that he doesn’t know me from a cord of wood. Now happy as I am to maintain that status I think he does know me. He will, I think, remember me from my correcting him on two or three occasions when I have thought it important to do so. He will remember telling me just two or three weeks ago that his trochee, spondee and three iambs were a perfect iambic pentameter line. Dr Salemi is a highly intelligent man (just to show that nobody has the monopoly on patronising remarks) and I am absolutelyconvinced that his memory far surpasses that of any goldfish.

In a contribution to discussions on these pages I am described by C B Anderson as having [ill-advisedly] “picked a fight with Joseph S. Now his life’s a bloody mess.” It has seemed to me that some members of SCP are almost afraid of him, that he has a Svengali-like hold over others. Admittedly most of his exchanges I imagine will be banter or persiflage. But just because we may believe that a remark has been delivered as banter it does not give us the right to assume the speaker does NOT mean exactly what he has just said. Remarks like Mr Anderson’s are not very reassuring.

It looks like Peter Hartley is pissed off about something, even though it took him three full days to compose a reply.

As for my memory, all I can recall is commenting a few times on your work. You wrote some sonnets pertaining to the First World War, and I made two suggestions, of which you accepted one. The other you rejected on accentual grounds, and decided to stick with your improbably awkward line.

I then made some suggestion on a poem “Kinlochresort,” which you also rejected. Then I commented on something you had said on Anderson’s post “Delimitations.” It was not aggressive or argumentative at all against you.

Then I made two pertinent objections to two out of your six above-posted clerihews. This must have lit your fuse for some reason, since you responded rather testily.

Guess what, Hartley? I still don’t know you from a cord of wood.

You’re right about one thing, however. I do not employ banter or persiflage. I mean everything I say, and I mean it exactly. If you don’t like it, you can bugger off. Got that, matey?

I think that’s how they say it in Britain.

Mr. Hartley, thank you for the clerihews.

Mr. Salemi, thank you for giving me a good laugh!

And in honor of you both, two clerihews:

Mr. Peter Hartley

Restores the art quite artfully

So as not to seem artificially;

They play their part quite officially.

Mr. Joseph S. Salemi

Should be given a Primetime Emmy

For standing up for formal verse

On cue, no need to rehearse.

Thank you, Evan, for the advertisement. On learning that I had difficulty restoring works of art in anything more than two dimensions a newish colleague immediately riposted with the following:

A would-be restorer called Hartley

Can clean pictures really quite smartly

But objects with nobs on

He keeps leaving blobs on

And in corners he pokes only partly.

(He seems to have been unaware that “nobs” in this context usually begin with a silent K.)

Of course, this is more a limerick than a clerihew.

J Salemi – “Matey” is a friendly form of address over here so I suppose I should be flattered. “Bugger off” on the other hand is a bit coarse anywhere and a trifle prosaic for a university professor with a vocabulary as fruity as your own. You appear to live in a state of perpetual rage.

“Matey” was meant to be ironic.

Here’s something less coarse and hopefully less prosaic — a clerihew just for you:

Peter Hartley

Is someone whom you might know partly.

He fell off a mountain

So he started syllable-countin’.

1. I appreciate Mr. Hartley for bringing clerihews to SCP.

2. As Mr. Hartley points out, the humour of the comic biographic verse form invented by Bentley, the clerihew, lies in its purposefully flat-footed inadequacy… The number of accents in the line is irregular. I do agree with the pugnacious Mr. Salemi, the first line almost invariably ends with the name of the subject. [By the way, does he remind anyone else of the educators in Charles Dickens’ “Hard Times”?]

The finest clerihews likewise use awkward rhymes. Here is an example from Bentley:

“Steady the Greeks!” shouted Aeschylus.

“We won’t let such dogs as these kill us!”

Nothing, he thought, could be bizarrer than

The Persians winning at Marathon.

3. A final example comes from the winner (Maia Wise) of a clerihew competition at National Review in February of 1991 posted by John O’Sullivan.

Remember Salman Rushdie

Though he wouldn’t be hushed, he

Has chosen astutely

To defy the imams mutely.

4. As to Mr. Tweedie’s question, some PostEliotic Postmodernist comic poets include, inter alia, Ogden Nash, Roald Dahl, Theodore Seuss Geisel, Shel Silverstein, X. J. Kennedy, and Wendy Cope.

5. Although written prior to Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939), one of my favourite American limericks is that by Dixon Lanier Abernathy/Merritt (1879-1972):

A wonderful bird is the pelican,

His bill will hold more than his belican,

He can take in his beak

Enough food for a week

But I’m damned if I see how the helican!

6. When I was young, I thoroughly enjoyed Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes; At the beginning of the New Millennium, I used their wonderful cadences in an unpublished book on American writers which I entitled “Brother Bruce’s Cursory Crimes”. One example of over one hundred pieces of nonsense suffices,

“Hey diddle diddle

Charles Peirce played the fiddle;

William James jumped over the tune.

Santayana sighed

to see such sport,

and Josiah Royce stayed up on the moon.”

Dear Wic E Ruse Blade – Thank you very much for your comments and interesting information on humorous verse. I too have always liked the one about the pelican but had no idea where it came from. And oddly enough a couple of months ago I wrote a little quatrain about Aeschylus, and had half meant to let this one masquerade as a clerihew too:

Poor Aeschylus is dead. It has been said

An eagle dropped a tortoise on his head.

Just think what he could have taught us

About probability theory and the tortoise.

Gradgrind, I’m afraid, would have had a lot of catching up to do: this educational system doesn’t involve any old facts and statistics: we are talking dochmiacs and anapaests, proceleusmatic feet and trochaic trimeter, the mechanics of composition but excluding such passe matters as beauty in nature, aesthetics, artistic creation and poetry as its mode of expression.

Bruce, although I appreciated your reference to my questions, and I appreciated the examples you gave of humorous poets since Eliot, my question specifically referenced “free verse” poetry, which does not include your examples. In a way, it serves to underscore my point, which was that it is difficult for free-verse poetry to carry the same humorous impact as is possible with limericks, for example.

Here is one of my attempts at a humorous free verse poem:

Hunger Games

The interview went well

quite well indeed until

I started chewing on my foot

all the way up to the knee

I should have anticipated that

at least for companies hoping

to hire an entire person

self-cannibalization

is a hard act to swallow.

I would still welcome examples of free verse humor.

It is possible to write comic poems in free verse, as the work of Ogden Nash and E.E. Cummings has demonstrated. But the core problem is that free verse is still emotionally tied to the sick mindset of modernism, which is fixated on High Seriousness, confessional revelation, and the pomposity of Portentous Hush. It isn’t easy being funny when you are in thrall to that gaseous trinity.

The best way to write comic free verse is to parody modernist stances, by expressing silly and bathetic ideas in the tone of High Seriousness that modernism reflexively uses. Try this:

I was crossing the street yesterday

and I had this epiphany:

the whole world had morphed

into oneness

and I too was one

with the entire cosmos

and everything seemed great

and I felt good

until a beer truck hit me.

That’s the kind of bovine excrement that modernism favors, and when you add that last line of bathetic parody you undermine the entire modernist project.

Mr. Tweedie’s “Hunger Games” is a nice comic bauble. Notice the first four lines are iambic trimetre, iambic trimetre, iambic tetrametre, iambic trimetre (with a lead-in anapest), but in the second section (I dare not call it a stanza.), he wanders about. However, in reference to his remarks on “Possum’s Book of Practical Cats”, I wonder if Mr. Tweedie is talking about the same book of T. S. Eliot’s as I am.

“The naming of cats is a difficult matter,

It isn’t just one of your holiday games;

You may think at first I’m as mad as a hatter

When I tell you a cat must have three different names…” etc.

One of the most astute observations I have read @ SCP about Eliot’s so-called free verse is that by G. M. H. Thompson who pointed out that Eliot was “being unfairly blamed for the free verse unpoetry that currently dominates the empty stage”. I do miss his impassioned literary critical remarks.

In Eliot’s essay “Reflections of Vers Libre”, Eliot writes: “It is assumed that vers libre exists. It is assumed that vers libre is a school; that it consists of certain theories; that its group or group of theorists will either revolutionise or demoralise poetry if their attack upon iambic pentameter meets with any success. Vers libre does not exist…”

I understand what Eliot was saying here—mainly that one cannot write poetry without prosody. In English, we accent any verbal construction of two syllables or more. I remember in my youth when I used to accent prose paragraphs; so much so, that even now, when I am reading prose, I frequently accent the syllables of the words I read.

Part of the humour of a limerick, not so much a clerihew which doesn’t lend itself to such predictability, is the inevitability of its progression from two longer lines via those two short ones to its climax or punch-line, following an inexorable rhythm and a pattern with which every schoolchild is familiar. I have never tried it, but surely it must be more difficult, by the very nature of vers libre (free, but still bound by rules) to achieve this. There is always the exception, even among limericks, to this inevitability of course:

There was a young man from Milan

Whose limericks never would scan.

When told this was so

He replied “Yes I know, but I always try to get as many words into the last line as ever I possibly can”.

Was that you . . or someone else?

Bruce, Yes, indeed we are discussing the same Eliot text. I however, misarticulated (isn’t that a great word!), and fully acknowledge Eliot’s thoroughgoing foray into rhyme and meter with “Cats.” I also enjoyed and appreciated your bulls-eye quote from Eliot’s essay re vers libre. Since reading your comment I have listened to myself speak in conversation with my wife. I believe I am inclined to iambic speech patterns. Interesting thought . . .

For Dr. Salemi, Thank you for the example of cummings whose free and witty whimsical verse did, occasionally, sneak in a rhyme to enhance the humor. As for Nash, I cannot recall a poem that did not include rhyme and at least some modicum of meter. Then again, I have not read them all!

I fully agree with your rationale for why free-verse, modernist poets, are near hitless when it comes to humor.

I never knew, ‘fore last week ended,

Of such a term as Clerihew.

When to that word my eyes attended,

My first response was ‘Cleri who?’

Monty, the best thing about clerihews is that they are very easy to compose. You get a good start just by writing the name of the subject, usually in full, on the first line and then think of maybe just one fact about that person and just go where the poem takes you. Your offering above is almost a clerihew but they usually rhyme AABB, not ABAB.

The above effort weren’t an attempt at a Clerihew, Pete. I’ve only just learnt of the form; and I’d rather be better acquainted with it before any personal essais.

The above was just a lined way of declaring my lamentable ignorance for most things technical and obscure concerning poetry.

Would you kindly quench my veritable curiosity by telling me the author of the above piece concerning the word-surplus man from Milan. Is it P. Hartley or A.N. Other?

The above effort weren’t an attempt at a Clerihew, Pete. I’ve only just learnt of the form; and I’d rather be better acquainted with it before any personal essais.

The above was just a lined way of declaring my lamentable ignorance for most things technical and obscure concerning poetry.

Would you kindly quench my veritable curiosity by revealing the author of the above piece concerning the word-surplus man from Milan. Is it P. Hartley or A.N. Other?

Sorry Monty, I think it’s the only one of my contributions that isn’t, and I have no idea where it comes from. It’s a limerick of course, and I’m not absolutely sure but I think they ALWAYS rhyme AABBA

Thanks Peter, for introducing us to the humorous Clerihew form. Some of the responses have also been quite informative, including Mr. Blade’s attribution of the delightful ‘A Wonderful Bird is a Pelican’ to Dixon Lanier Abernathy/Merritt. I also wondered where this originated.

In the spirit of whimsy and mirth I add:

The kangaroo has a trick or two,

Including a powerful punch,

A foot requiring enormous shoe,

And a pouch to stow her lunch.

Thank you for that, David, and that was a new one on me. A thing I’ve found about limericks and even more with clerihews is that they don’t take long to write. I think I can remember doing half a dozen in a couple of hours, and that is very fast for me, where I might take two days or more tweaking a sonnet. Finally, how about this then; this one is really a bit of a cop-out in that once you have the idea the rest is easy:

Friedrich Nietzsche

Had only one interesting fietzsche.>

Spelling the name of this crietzsche

Defeated his philosophy tietzsche.

Is this a clerihew?

Dominic Cummings told many lies

About the state of his bulbous eyes

Taking a trip to Barnard Castle

Cementing his status as total arsehole.

Yes it IS a clerihew if we can accept that the castle rhymes with Dominic Cummings’s arsehole, in which case the rhyme scheme is AABB which is the typical, though not invariable, rhyme scheme for a clerihew.The uneven line length is also typical of the clerihew form.