Gilgamesh Lines

Introduction

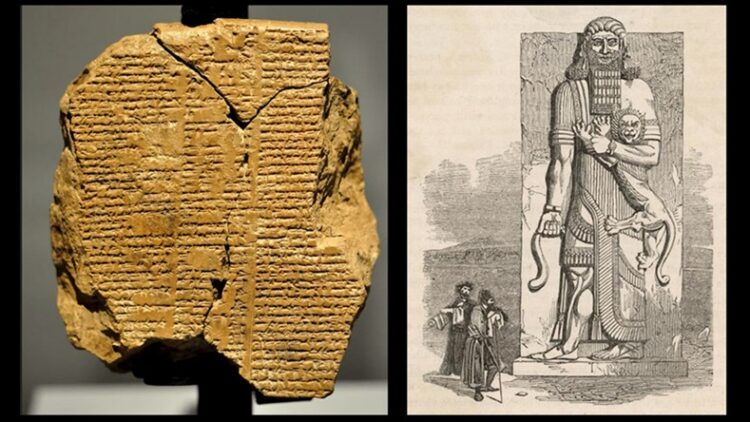

In 2011 when we were evacuating Iraq, looted antiquities entered the market. One such was this shard which features 20 partial lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh, likely inscribed before the seventh century B.C.

Verse translation “I” occurs early in the epic. Verse translation “II” occurs slightly farther on. Together the translations bracket a notion of civilization, “wildness and taming.”

Because incomplete, because versions of Gilgamesh differ in particulars, and because cuneiform writing allows broad, sometimes divergent interpretations, there is not a single definitive version of the epic. Then too, this recent Kurdistan text (Neo-Babylonian) follows the more ancient texts from Uruk (Late Babylonian) and Ninevah (Assyrian).

Three characters worth noting: The anthropomorphic giant, Humbaba, spawns the forest “demon-trees” that he rules and guards; Enkidu is an anthropomorphic man, companion friend of Gilgamesh; Gilgamesh is Sumerian, possibly an actual king of Uruk (2900–2350 B.C.) whose legends are recorded in five surviving cuneiform documents that together form the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Between these translated episodes, Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the Bull of Heaven. Enkidu for his part in the slaying is condemned to death. Because Gilgamesh witnesses his friend’s mortality, he unsuccessfully seeks immortality and is resigned to death, and that’s the span of the epic.

I’ve inserted two details which resolve the translations into a poetic whole. Enkidu is inserted into “I” and Enkidu’s physical characteristics are inserted into “II.”

I.

A bird begins to sing and soon

Answers echo through the forest,

Some in and others out of tune

Join the merry dinning chorus.

A pigeon moans, a wood dove coos,

A cricket crickets on a leaf,

A stork exults, a booby boos,

Monkey youngsters at mothers shriek.

The cedars sway in Lebanon,

The drummers drum and horns hurrah,

A weary Enkidu does yawn

Before the mass of great Humbaba.

II.

Bull tailed Enkidu opened his man-mouth

To speak these words to Gilgamesh, “My friend,

We have reduced the fertile forest to

Wasteland. How to tell Enlil in Nippur

That hero-like you slew his guardian.

My friend, what was that all-consuming wrath

That trampled down the trembling forest?”

Michael Curtis is an architect, sculptor, painter, historian, and poet, who is currently Artist-in-Residence at the Common Sense Society. He has taught and lectured at universities, colleges, and museums, including The Institute of Classical Architecture, The National Gallery of Art, et cetera; his pictures and statues are housed in over four hundred private and public collections, including The Library of Congress, The Supreme Court, et alibi; his verse has been published in over thirty journals; his work in the visual arts can be found at TheClassicalArtist.com, his essays at TheStudioBooks.com, and his architecture can be found at TheBeautifulHome.org.

What a fantastic fragment. The details about the animal sounds are very charming. I believe this same forest of cedars was also used to build Solomon’s Temple, which makes it perhaps the most distinguished forest in literary history? Well done, Michael!

Yes, isn’t it. Andrew, did you know that Solomon’s temple columns are mere niche frames set into the walls of Saint Peter Basilica, dwarfed by Bernini’s magnificent baldacchino. More to discuss when next we speak.

Any little insight into this precious ancient work is worthy of appreciation. Yours, Michael, by weaving two fragments together, offers an interpretation to stir the imagination. I can imagine more of the epic battle carried on by two devoted friends.

The text easily lends itself to creativity such as you respectfully show in these beautiful verses. I recall Enkidu as hero-king in a fantasy novel written by one of my graduate school friends who, going much further afield, created a full range of characters. She ultimately left the study of classics for a successful career as a book illustrator, always much in demand by authors.

Yes, Margaret, beautiful little fragments are worthy of illustration in words and pictures. Hmm. Wonder who that illustrator friend is?

Her studio name is Pyracantha, and you can find some of her art at a website by that name. She did architectural renderings, too, and the piece of hers that I own is a detailed drawing of a Victorian house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, made for me and my husband to remember the neighborhood of Harvard’s Conant Hall. Sadly, she seems to have gone offline and into rehab during the past few years.

The more we find of the Gilgamesh epic, the more important it appears. Yes, there are many versions, with significant additions and variations to the main story. The same must have been true for the Iliad, before it was written down and standardized by scribes in the eighth or ninth century B.C. The Iliad survived because Greek culture survived; Gilgamesh had to wait until the 19th century A.D. before it was rediscovered and translated.

When I taught the Ancient Cultures class at NYU I always assigned the Gilgamesh text, because it is absolutely indispensable for understanding how the building of great cities was at the very heart of nascent civilization. And the concomitant developments were the absolute conquest of nature, and the forcing of nature to serve human ends. The making of bricks, the erection of great walls and palaces, the massive logging of wood from virgin forests, the full-scale domestication of animals for food and transport, and extensive agriculture — all these things are celebrated in the Gilgamesh epic. As I told my students, the epic is a sure-fire antidote to mindless environmentalism, animal rights fantasy, and tree-hugging conservationists. Human beings build great cities, kill wild and tame animals, and cut down forests.

The killing of Humbaba by Gilgamesh and Enkidu is the triumph of active, civilizing men over the savage darkness of nature and the wilderness. Both Gilgamesh and Enkidu suffer for it, since they have angered the gods. But despite death they gain what is called “imperishable fame” in both ancient Greek and Sanskrit, in a verbal formulation that goes as far back as our Indo-European ancestors.

Exactly.

Just now engaged in that civilization building bit.

I look forward to sharing, soon.

Captivating!

Thanks.

Fabulous work: every fragment we can access, translate and gain from this primal time is so valuable in helping us understand that ‘first time’ and what it tells us about humanity. “How to tell Enlil in Nippur …” indeed, one longs to know how!

Yes. And how very little we have changed.

Michael, your versification is very successful in giving life to what is usually represented as colorless prose (which is how I read the extant text some 55 years ago). Fortunately I had a Humanities professor who shared some of the same germinal significance as so cogently shared by Dr. Salemi. My class also covered Beowulf, Iliad/Odyssey, Aenead, and Song of Roland. All good stuff. Code of Hammurabi and Gilgamesh were covered in a sophomore high school world history class. What a great way to learn history, from original texts rather than textbooks!

Puts us all in context.

Forgive me for taking so long to comment. These verse translations make the text come alive as I have not yet read before (i.e. a poetic, versus an academic translation). You set the story in rhythm and rhyme (at least for I), with nice redoubling effect (“booby boos,” “crickets cricket”). I love seeing ancient literature come to life like this.

I would love to see a transliteration of the original to see if the repetition and sounds you use mirror the original text. (And I would like to know which language the tablets were in — from a 7th c. B.C. date I’d assume Babylonian – if in southern Iraq – but maybe it was preserving Akkadian or Sumerian. I’d love to know.)