Longfellow

I first met you in the schoolroom,

_When I was but a child,

And read your words and heard your voice

_Sing out so sweet and mild.

But as I grew, I saw your work

_More cast off and despised,

By those critics who now believe

_History should be revised.

So they call you sentimental,

_Like innocence were a crime,

And wash with a wave of insults,

_Your name from the sands of Time.

And they say you are too simple,

_Too straightforward, lacking flair,

As if it were ever easy,

_Choosing Hope over Despair.

As if the Truth should be obscured,

_Guarded by a select few,

And is something that the common

_Man should never hope to view.

Like conviction were a weakness,

_And clarity a sin,

And instead of your bright music,

_They prefer the dark and din

Of formless Vanity, in whose

_Dim shadowed shroud they hide,

And they mock those who tell stories,

_Sitting by the fireside.

Can’t they feel the embering soul,

_At your verses rise and swell?

Can’t they see the light of Heaven,

_Runs far deeper than their Hell?

When you write old-fashioned Virtue,

_They count it as a flaw,

They realize not they fault the man,

_Who saw what Dante saw.

The tower that you built with rhyme,

_The human heart to hallow,

Blames more the reader and not you,

_If they should find it shallow.

Some dismiss you still as childish,

_And some still call you fraud,

Forgetting that only children

_Form the Kingdom of our God.

For Truth and Wisdom are profound,

_E’en more so when they’re plain,

And will brighter grow, yet brighter,

_When they are read again.

Lovers of confusion, who at

_Your life so often jeered,

Cannot see the fiery scars burned,

_Beneath your snowy beard.

But are maddened flocks of sea-birds,

_Always raging like a squall,

Up against the flaming lighthouse,

_Unperturbed and standing tall.

For your words, like church bells, teach us

_As they’re ringing out their song,

How to suffer, and to suffer,

_And to suffer and be strong.

Kevin Parks works as a data analyst in Ogden, Utah.

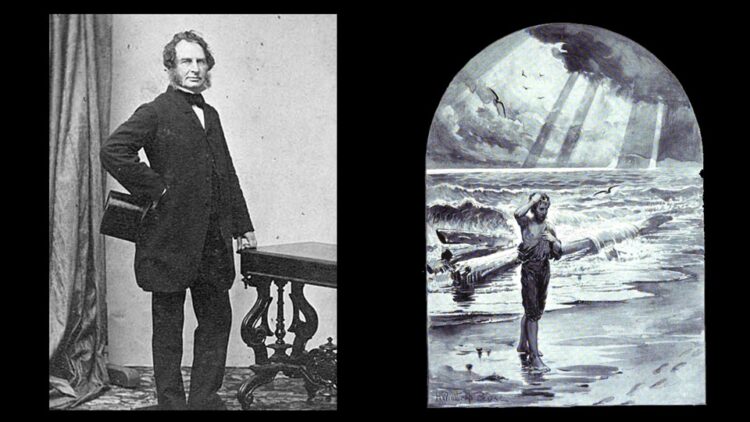

Longfellow was certainly a top-rank poet and translator, recognized in his own country and in Europe as a master wordsmith. And as this poem says, he did suffer intensely, especially after the accidental death of his second wife.

The reason for his decline in status (as measured by the academic establishment only; plain readers have never ceased to appreciate him) was contextual. He lived to the close of the nineteenth century, and a major rebellion against Romanticism and Victorianism was starting to heat up at that time. Whitman came along, the shocking Swinburne came along, the English Decadents and Pre-Raphaelites came along, and the first hints of Modernism were starting to be scented. It was in the cards that Longfellow should become a target, as also happened to Tennyson. By any realistic standard both of these men were great, but in a literary world where complete upheaval was being preached as the new ideal, the more staid and conventional predecessors were laughed at and ignored. Also, academia has had a longstanding hard-on for modernism and experimentalism and generalized freakiness since 1922. It has now become mummified in its obedience to the “make it new” mantra.

There’s also the snob element. If simple people can read and recite and enjoy a poet like Longfellow, how good could he possibly be, sneers the average English professor along with his colleagues. They say the same thing about Kipling, whose talent is deliberately being badmouthed today, for political reasons.

The poem by Kevin Parks struck a chord. I am one of those “plain readers” who still enjoy reading Longfellow. I met (and thrilled to) his poetry in school with “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” one of the poems in “Tales of a Wayside Inn.” Yes, it wasn’t historically accurate, but accuracy mattered less to a nine-year-old schoolboy than the emotions of urgency and courage it aroused. Later I read “Evangeline,” which, me being from south Louisiana with a flock of Cajun relatives on my mother’s side, seemed more like personal history than poetry. I never lost my fondness and admiration for Longfellow, and I recently reread all of his major poems. I still enjoy them.

Kevin, I’m delighted you wrote this. Longfellow was my gateway into poetry. I knew nothing about the art form, but was captivated the first time I read his work. The first lesson I pulled away was that beautiful work can often and immediately be appreciated on its own merit. The second was that I need to find and read more great poetry!

Thanks, Kevin: it’s truly a pleasure to see Longfellow celebrated like this. As a resident European, I’m acutely aware that HWL knew and understood Europe better than many of its inhabitants. And I agree totally with Dr Salemi’s assessment of his place in literature and the damaging effects of literary fashion.

Kevin, not only are you defending Longfellow, but your own composition of poetry has an engaging flow!

I, too, am a major Longfellow fan, Kevin, and especially Kipling. I’m a diehard (75-year-old) Populist poet and I read (for free) at a slew of care centers every summer here in eastern Iowa, and I often hear comments like: “Now that’s what I call poetry.”, and, “Finally – pieces I can easily understand and sometimes even relate to.” My audiences are admittedly peppered with only handfuls of over-60- listeners, but, as many of us know, more than a few other HWL-advocates are among the most successful poets penning ‘Verse’ today, both old and young, as poetry-book-sales prove. Thanks for sticking up for him. 🙂 This little diddy was obviously inspired by Rudyard himself –

When

When, my son, you’ve learned to focus all your hate and anger

and implement the net of all your skill

To spare the man you disagree with, opting not to join

the ranks of those whose preference is to kill –

When you’ve come to realize that helping those in need,

and – showing those who suffer that you care

Fills your heart with joy and answers questions in your mind

of which the ones who don’t are unaware –

When you’ve learned the reason why some people feel obliged

to bow their heads when dignitaries pass,

And then reject it wholly by adopting this belief —

that no one on this earth is second class –

When you’ve grasped the difference twixt the way we look – outside –

provides you no excuse of any kind

For treating others hatefully, and see your fellow man

through eyes that you can boast are color blind –

Only then can you expect to win your bouts with life…

which you’re, of course, the only one that can…

For each of these will strengthen you, and fortify your soul,

and which is more, my son… you’ll be a man!

I’m not that knowledgeable of Longfellow – just the usual suspect, The Song of Hiawatha – but will definitely give Paul Revere (my namesake) a try. I am a fan of narrative poems, having written so many in the past.

It’s interesting what Joseph said about why Longfellow went out of fashion. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes was immensely popular, but was a product of the Victorian era, of horse-and-carriages and new stories, in the rising era of the motor car, just didn’t fit the bill. That said, the nostalgia of Victorian times is encapsulated in the various adventures of Sherlock Holmes to this day.

Thanks for the read, Kevin.

Paul, I believe Conan Doyle and Kipling were popular for three reasons: 1) They had amazing talent as writers; 2) They were new on the scene, as opposed to older types like Longfellow and Tennyson; and 3) They dealt with very real and contemporary subject matter. Conan Doyle’s stories were about crime and mayhem and detective work in London, and Kipling’s poems and stories were largely about the adventures of British soldiery in the Indian Raj. They were perfectly suited to a newly literate public of common readers in Britain and in the U.S. Also, Kipling could use the rough and colloquial speech of the iconic British soldier (“Tommy Atkins” was the name for him, just as “G.I. Joe” is for the American soldier). This gave his work a wider, democratic appeal. The Sherlock Holmes stories were a hit because they were so damned interesting, and remain so right up to now.

I am still somewhat new to poetry, but I have read a few Longfellow poems that I thoroughly enjoyed. I hope to read more of him in the future.

Your ode to him was great, and makes me want to read his poetry; since I do enjoy clear and straightforward poetry.

Kevin, your poem shows you quite capable of appreciating Longfellow and of telling why critics scorn his work. You praise good storytelling and manly virtue and simple sentiment and the light of heaven. Bravo! This is what I remember from early hearing and reading and memorizing, and from reading Longfellow with my children in homeschool. By then I was better able to value the artistry of his language, and to talk about how he distinctively treated each of the particularly fascinating subjects he chose for longer poems. I like your honest advocacy.